Read Dare to Be a Daniel Online

Authors: Tony Benn

Dare to Be a Daniel (7 page)

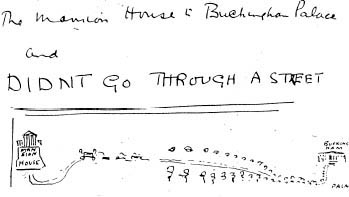

He drove him from the Mansion House

The Mansion House

The Mansion House

The Mansion House to Buckingham Palace

And didn’t go through a street.

Father once said to me, ‘Never wrestle with a chimneysweep’, which was a curious piece of advice to give an eight-year-old, but I now understand exactly what he meant: ‘If someone plays dirty with you, don’t play dirty with him or you will get dirty, too.’ My attempt to keep personal abuse out of political controversy has been shaped by that simple phrase about how to steer clear of chimneysweeps. I recommend it to others without reservation.

Father had inherited a distrust of established authority and the conventional wisdom of the powerful, and his passion for freedom of conscience and his belief in liberty explain all the causes he took up during his life, beginning with his strong opposition to the Boer War as a student at University College London, for which

he

was, on one occasion, thrown out of a ground-floor window by patriotic contemporaries.

He had been sent to France with his brother Ernest in the 1880s and learned to speak French fluently. When he wore a beret, he looked very Gallic. He studied French at university and, after leaving with a first-class honours degree, lived in East London and worked as a journalist for

The Cabinet Maker

, the journal founded by his father, which later became part of Benn Brothers’ publishing concern.

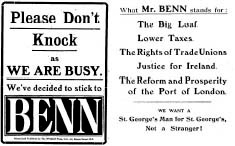

By the turn of the century Father was already active in Liberal politics in St George’s constituency in Wapping, helping to raise funds for cigar workers locked out in their industrial dispute. He won the unanimous support of the Municipal Employees Union and of Stepney Labour Council when he was adopted as a Liberal parliamentary candidate for Tower Hamlets.

In his 1906 election address he criticised the Tories for ‘having made laws for the benefit of their privileged friends and entirely neglected the claims of the workers’. He pledged himself to support legislation ‘to protect the funds of trade unions, to support Irish Home Rule and to work for the establishment of a national home for the Jews’, helping Jewish refugees who had fled to East London from the pogroms in Tsarist Russia at the end of the nineteenth century. He made his maiden speech in the House of Commons arguing for the municipal ownership of the Port of London, drawing attention to the rising unemployment among dock workers.

After serving as a Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) to Reginald McKenna, the First Lord of the Admiralty, in 1908, Father was made junior Whip in 1910 and carried the responsibility for answering questions in the Commons for the Office of Works, because the First Commissioner of Works, Earl Beauchamp, was in the House of Lords.

In 1914 he volunteered for the Middlesex Yeomanry, although both his age (then thirty-seven) and his membership of the House of Commons would have exempted him from military service. For the next four years he served in the forces fighting at Gallipoli, flying as an observer in sea planes from a passenger ship, the

Ben-My-Chree

, which had been converted into an elementary aircraft carrier. When the

Ben-My-Chree

was sunk by Turkish gunfire, he commanded a small Anglo-French force, holding out in Castellorizo. Later, aged almost forty, he qualified as a pilot and served on the Italian front, where he flew on the night mission with Tandura, the first spy ever dropped by parachute behind enemy lines in Italy.

He once described how he took a saw and cut a hole in the bottom of the plane so that Tandura, the Italian chosen for this operation, could be launched with his parachute and a box of pigeons – being released at an agreed moment when Father pulled the lever that allowed him to fall out of the plane.

Tandura undertook this immensely dangerous task, landed safely and reported on enemy positions by scribbling them on little notes, which he tied to the legs of the carrier pigeons, which then flew back to Headquarters with their important intelligence information. Tandura survived, and after the war named his own son Wedgwood Benn Tandura. I have often thought of an ageing Italian who must have asked himself why he had such a ridiculous name.

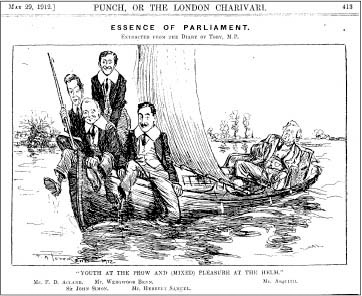

A

Punch

cartoon showing Father and some young Radicals with an anxious Prime Minister.

Punch

wrote:

House of Commons, Monday, May 20

: To-day we have with us only one

BENN

, upon whom his godfathers and godmother in his baptism, with prophetic foresight of what in due time would become a precious antique ware, bestowed the name of

W

EDGWOOD

. The twentieth-century

L

ITTLE

B

ENN

ranks in Ministry as Junior Lord of Treasury, his place being in the Whips’ room or the lobby.

P

REMIER’S

quick eye discerning his capacity, he has this session provided for him a seat on Treasury Bench, where he represents

F

IRST

C

OMMISSIONER OF

W

ORKS

, throned in the Lords.

Father was awarded the DSO and the DFC, the Légion d’honneur, the Croix de Guerre and an Italian decoration which he called the ‘Fatiguera di Guerra’ and translated as ‘Sick of the War’.

For him, public service in wartime meant military service and he refused two invitations from Lloyd George (who, by December 1916, had become Prime Minister) to join the government, first as a Parliamentary Secretary and later as joint Chief Whip in the wartime government.

Father’s wartime service helped to develop his political philosophy, and his book

In the Sideshows

, about those years in the services, throws some light on it. He saw the old professional army officer as being incapable of ‘appreciating the diversities of human character and capacity’ and as discouraging ‘initiative and energy through class prejudice determined to entrench itself’.

He wrote, ‘There are no regulations to say that none but the privileged class is permitted to enter; the existence of class barriers is denied; but those who have been on the inside know perfectly well that the gate is strictly kept.’ And he noted the ‘inevitable ignorance’ of officers who ‘live in narrow grooves and are forbidden by the rules of the game to receive any education from those who alone can educate them, namely their subordinates’. ‘Wars are peoples in arms,’ he argued:

Leaders are needed, military as well as political, who see the difference between a just and an unjust cause; who understand how

much

ideals count as a practical force, even in the behaviour of individual soldiers; who know that Right is the steam which drives the engine Might.

His experience also made him into an internationalist. It was the war that drove him on to promote international understanding.

On his return home in 1918, he discovered that his constituency had been redistributed and another Liberal candidate was in place. Rather than fight it out, Father accepted a nomination as an independent Liberal for Leith, in opposition to Lloyd George’s coalition, and was elected. The next eight years were ones of vigorous parliamentary activity with the Radical group that he jointly led, and it was during those years that he developed his skill as a debater and his reputation as a parliamentarian. He was bitterly opposed to the government’s Irish policy and to the use of the ‘Black and Tans’ against the Irish Nationalists.

In 1920 he moved an amendment in Parliament to the King’s Speech, condemning the Coalition for having handed over ‘to the military authorities an unrestricted discretion in the definition and punishment of offences’ and ‘having frustrated the prospects of an agreed settlement of the problems of Irish self-government’. Though he had, earlier, been more attracted to Lloyd George’s radical reforms than to Asquith’s Whiggery, he deeply mistrusted Lloyd George as a person and detested his coalition with the Tories.

Finding himself voting more and more often with Labour MPs in the Commons, Father finally resigned from the Liberals in 1927 after Lloyd George was elected their leader. He joined the Labour Party, sat for a moment on the Labour benches and applied for the Chiltern Hundreds on the same day – a device used to effect an immediate

resignation

from Parliament. He thought it right to resign his seat because his constituents had elected him as a Liberal and he believed it was immoral to remain as a Labour MP, a precedent that few who have changed their party allegiance since have followed.

When he and Mother were visiting Moscow in 1926, they witnessed the trade unions marching with their banners in the May Day Parade. He loved to tell us how when he asked an interpreter to translate one of the revolutionary slogans, the answer was: ‘Workers of the Electrical Trades improve your qualifications’!

Though Father neither embraced the full socialist economic analysis nor was rooted in the trade unions, he greatly valued the fellowship that his membership of the Labour Party brought him and shared its seriousness of purpose. After attending his first Labour Party Conference in 1927, he wrote in the

Daily Herald

that ‘a great sense of responsibility seemed to overshadow the gathering … they were making decisions that in the near future would pass from being the resolutions of a Party to becoming the policy of the British government’. Until the end of his life his sympathies remained instinctively with the non-conformists within the Party, especially when attempts were made to impose Party discipline on them, being something of a lone crusader himself.

In 1928 there was a by-election in North Aberdeen and my dad was elected as a Labour MP and a year later was put in the Cabinet in Ramsay MacDonald’s second minority government, as Secretary of State for India. It was his first experience as a departmental minister and he had to defend himself in the Commons. Lloyd George, mocking Father’s short height, once taunted him as a ‘pocket edition of Moses’, to which he replied, ‘At least I do not worship the golden calf’ – a reference to the fact that Lloyd George had sold peerages to boost his own political funds.

Working towards ‘Dominion status’ for India, he came under heavy attack both from Churchill, the old imperialist who opposed the very idea of Indian independence, and from the Left, who believed that this policy was too slow, and disapproved of Gandhi’s imprisonment. But Father did succeed in calling two Round Table conferences and in bringing Gandhi to London as a delegate to the second one.

By the time it was held, however, the Labour government had fallen. In August 1931 Ramsay MacDonald had capitulated to financial pressures and had formed a National government. An interesting insight into MacDonald’s mind is given in a letter sent to Labour MPs dated 25 August 1931, justifying the cutting of benefit to unemployed workers, and saying:

… To restore the necessary confidence, as every one of us recognises, it is necessary to balance the Budget, and the problem is how to spread the burden involved equally throughout the community … During the past weeks events moved so rapidly that widespread consultation was impossible but I hope you will suspend judgement until the situation has been made clear to you and the facts put in your possession.