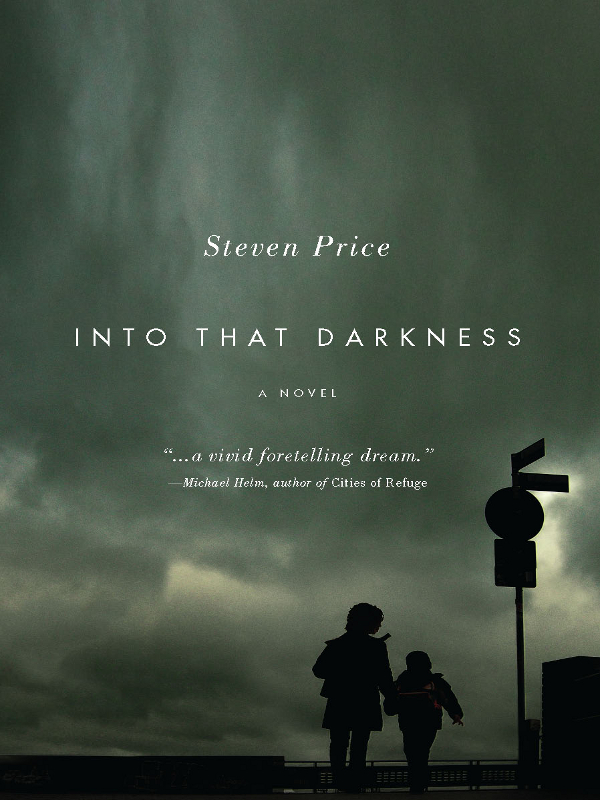

Into That Darkness

INTO THAT DARKNESS

INTO THAT DARKNESS

Steven Price

a novel

THOMAS ALLEN PUBLISHERS

TORONTO

Copyright © 2011 by Steven Price

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any meansâgraphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systemsâwithout the prior written permission of the publisher, or in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Price, Steven, 1976â

Into that darkness / Steven Price.

ISBN

978-0-88762-737-8

I. Title.

PS

8631.

R

524

I

57Â Â 2011Â Â Â Â Â

C

813'.6Â Â Â Â Â Â

C

2010-907346-0

Editor: Patrick Crean

Cover design: Michel Vrana

Cover image:

kallejipp/photocase.com

Published by Thomas Allen Publishers,

a division of Thomas Allen & Son Limited,

390 Steelcase Road East,

Markham, Ontario

L

3

R

1

G

2 Canada

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the support of The Ontario Arts Council for its publishing program.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $20.1 million in writing and publishing throughout Canada.

We acknowledge the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporation's Ontario Book Initiative.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (

CBF

) for our publishing activities.

15Â Â 14Â Â 13Â Â 12Â Â 11Â Â Â Â Â Â 1Â Â 2Â Â 3Â Â 4Â Â 5

Printed and bound in Canada

Text Printed on a 100%

PCW

recycled stock

for Esi

Who can tell what purpose is served by destinies

And whether to have lived on earth means little

Or much.

â

CZESLAW MILOSZ

This book would not exist without the extraordinary grace of Lise Henderson. For advice, support, and encouragement, I am also grateful to John Baker, Jeff Mireau, and Anne McDermid; to my family, Bob & Peggy, Brian, Kevin Potato; to Patrick Crean, for his judicious eye; to Jack Hodgins, for his wisdom and friendship; and especially to Jacqueline Baker, who is, as ever, a light and a reason.

CONTENTS

The child was breathing quietly at the parlour cabinet, his teeth glinting small and sharp in the half-light.

It's alright, his grandfather said. Go ahead. Open it.

He looked up.

His grandfather's shaggy head, upraised and watching. A law-book clutched in one fist, a knuckle marking the page. When the old judge shoved back his chair and walked over and ran a hand along the child's neck his seamed palm felt ghostly and cool. What you're looking at there would be a million years old at least, he said to the child. The oceans were once full of them. He fumbled with the book in his fingers. Your father found it for me. Do you know where he found it? Under the trestle in Sooke. In the mountains.

In the mountains?

In those days all this was under the ocean. Even the mountains.

The child cradled the fragment of shale in his hands with great delicacy. Its surface was small and very black and tattooed upon it was a tiny black chambered shell spiralled like a goat's horn.

His grandfather took the fossil from his open palm and stooped looking down at it. I once thought it was very valuable, he said. I thought myself lucky to have found it. For it to have come down across so many millennia to end up here, in this room, in my hands. Can you imagine. It's a piece of a vanished world, Arthur, a world that will not come again. Wouldn't you think that's worth something?

The child nodded. Yes sir.

His grandfather cleared his throat as if from a long way off. Set the fossil down again on its shelf. He shut the cabinet fast and the glass door pinged as it shivered to. Well, he said. I guess I did too. I guess I keep it as a reminder. Of another kind of law. He clasped his hands in the small of his back and leaned in and peered at the fossil as if to read a secret writ upon it.

There have been many ends of the world, he said softly. This was one of them.

I'll be buried here too.

You don't think about that when you're young. Or it isn't the same

somehow. I was born in this city and I'll be buried in it. My parents are

buried here, and my grandfather, who raised me. He was a big man, his

skin was grey as old paper. He served as a judge for half his life. He considered

it a kind of duty. He told me a question doesn't have to be something

you ask. It's a way of looking at the world. I don't know. I guess

I've tried to look at the world like that. It's strange to think he was

younger than I am now when he died.

I go out to his grave sometimes to pick off the dead flowers, lay a fresh

bouquet. I think the dead deserve more from us. That might just be my

age talking. My eyes drift over the low iron fences, the crumbling monuments,

the shady tree-lined paths to the sea. The sea like wimpled

metal. The sea with its terrible coins of light. I don't like to look at it now,

it hurts my eyes.

When I go to his grave I think mostly about my own life. What I

didn't achieve. What I didn't hold on to. The work I might have painted,

but didn't. Not about what's come apart down in that darkness, the

wood planks, his second-best blue suit that looked so green in the coffin.

His body. I don't know if that's selfish or just the way we're built. Maybe

a bit of both.

Two years back I remember going out to his grave and finding the

stone overturned, broken at its base. Someone had spray-painted something

on the stone I couldn't read. It was in purple paint. I guess it was

kids. You see them sitting on the streets begging for change, or running

out to wash windshields at intersections. They have hard eyes, flinty eyes.

Still I don't know what would make a kid do a thing like that. I don't

understand it. I guess we must have been that way too once. But we never

desecrated the dead. We never would have done that.

I looked a long time at that mess.

Callie always said I had a draftsman's eyes, not a painter's. I suppose

she was right. I don't know that I ever saw anything truly. I tried. I guess

you could say that was the real work. Seeing. Callie would have laughed

at that. She didn't think truth was something you saw. She said change

was the only constant in the world, and it was change she wanted to find

in her sculptures. She saw with her hands, her fingers were her eyes. Callie

had enormous hands. Her palms were always hot. She would put them

on my naked back in bed and it would be like a furnace. I can still feel that

heat. The pressure of her knuckles, like she was shaping me as I slept.

We were young together once. It's strange to think about now. I

could have gone after her I guess. I could have left too. I don't know. She

wanted so much to love, it was as if she loved. It was never enough for

me. I wonder if it would be enough for me now.

His wife did not die in autumn and yet autumn was when he dreamed of her. He sat on the edge of his bed, an old man now and coughing in the darkness, white sheets tangled at his waist. His dead wife blurred and fading from the curtains. He sat and he coughed and he rose.

On the stairs his bare feet tracked moist half-prints over the oak which shrank at once and were sucked up invisible. He wore pale corduroy trousers soft as the skin of a peach and a collared white shirt and a heavy silver watch on his left wrist. The big waist of his trousers was cinched tight with a belt notched to the last notch but one. When he came down into the kitchen the low sun in the east was red and the easterly sky red also and at the table he stood drenched in that light as in another man's blood and it was this light he saw by.

The cupboards were bare. He filled an old kettle and set it to boil on the stove and he took his mug from its hook above the sink. Unscrewed the lid of a white ceramic jar. Spooned out coffee and left the lid off and the spoon standing in it and when the water was boiled he poured and stirred and drank his coffee. It was the second Tuesday in September, the end of his sixty-ninth year. His name was Arthur Lear.

Some days he would speak to no other living soul. Some days he would scrape at his memories like charcoal, rub his past between dry fingers. This house had been erected in the third decade of the last century and with its arched ceilings and narrow corridors and weird arterial plumbing some days the pipes in the walls would mutter and hiss eerily like a chorus of the dead, and those ghostly voices would be the only voices he'd hear.

Days and days.

The old man took his greatcoat down from its wooden pin and went out.

Locked the deadbolt deliberately, pocketed the key. Then standing in the street he turned back to double-check the door. The grey cedar shakes on the sides of his house were splitting. Yellow spears of grass sprouted under the low casement windows, the boot-pulped porch steps slumped crazily. He had been a painter for most of his life and he wondered when he had stopped noticing such details. In the bay window he could see the shapes of old canvases, props, brushes fanned out in unwired jars. But that was all of another life. That was another life.

He went on up the street, his big hands curled at his sides like grey spiders. At the first intersection a black dog loped across the street some soft thing in its jaws and the old man watched it go. The streets were quiet here. His black shoes were clean but unpolished, their hard heels clicked softly. The sidewalks looked bleached and windblasted. An early sunlight was etching the very edges of things.

When he reached the neighbourhood pub he peered into the glass doors and ran a hand through his hair. Waited for a break in the traffic, jogged across to the bank on the far side. The coins in his long pockets swung heavily. The streets were filling with figures scarved and pale and moving with purpose towards parked cars, bus stops, the city itself. The old man glanced at the faces he passed but no one met his eye.

Then he turned the corner and peered across the street at the tobacconist's. Through the windows he could not make out her shape. Her shop fronted a square of shops and boutiques below an old wooden theatre and on the far side stood a bench and fountain where he would often sit and read in the mornings. Just beyond these a big oak tree thrust forth rooted and powerful from the cobblestones like a great upwelling of earth. In a café window next to the tobacconist's he saw a black child's face pressed against the glass, his thick plastic eyeglasses distorted and watery in the light, and then the boy was craning his neck upwards. Two women in tailored coats had paused beside the old man and were pointing at the sky and then a rushing sound like fast water could be heard and the old man too raised his eyes.