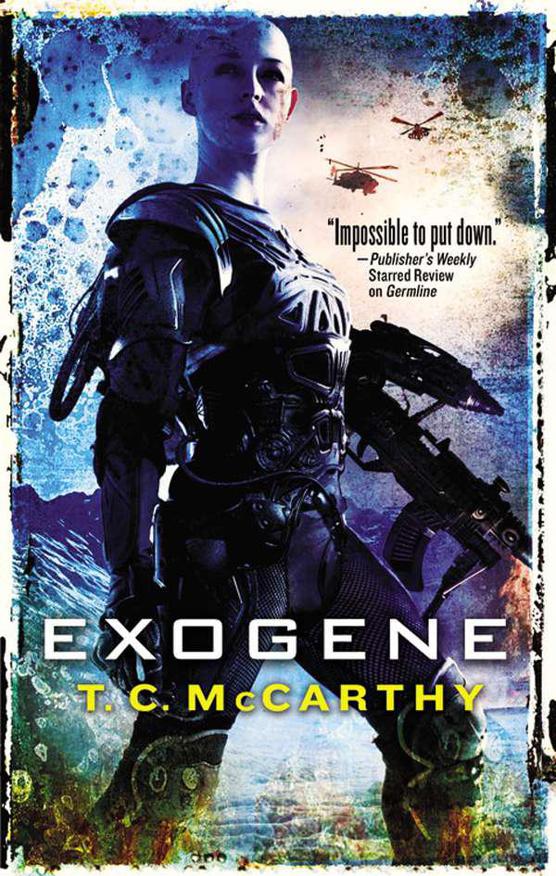

Subterrene War 02: Exogene

For Josh and Conor

Special thanks to Lou Anders who took me under his wing at my first WorldCon, and to John Scalzi for giving me a chance to participate in “The Big Idea.” Thanks also to Jack Womack—publicist extraordinaire—Alex Lencicki—also a publicist extraordinaire—and of course to DongWon Song and Anna Gregson for everything else that it took to write this book.

Y

ou

told me they’d welcome suicide,” General Urqhart said. “That once their service term expired, Germline units would march in like virgins, ready for their own sacrifice. But that’s not happening.”

His audience was silent. The general’s aides stood along the edges of a conference room while a group of scientists sat around a long table, and he stared at the holo-map that rotated overhead to show allied lines in blue, Russian in red. Nothing on the map moved; he didn’t expect it to. For now it was static, a car stuck in a ditch that they hadn’t yet figured out how to dislodge and with no sign of a tow truck. A disaster. If Urqhart didn’t retake the mines within six months, and hold them for at least three, the war would be a financial catastrophe and that was the problem with his scientists: they didn’t “get” war. Winning didn’t depend on holding territory anymore, it hinged on pulling as much metal from the ground as you could and then leaving at the right time, a strategy that depended on having every tool working. And now he had to reassign Special Forces when he needed them the most.

“We’re hemorrhaging genetics,” he continued. “The first fielded units reached the end of their term, and of those, sixty percent are going AWOL. Heading west into Europe.”

One of the scientists cleared his throat. “General, we already have reports of escaped Germline units dying before they can get too far. We just don’t see this as a crisis; safeguards are working.”

The rest of them nodded and some of the scientists even smiled, which made Urqhart furious. He pounded the table.

“Really? You don’t think there’s a problem? How do you think it looks to the public when news reports show disfigured girls in Amsterdam, Ankara, even Norfolk? What do you think the public sees? Not the military. They see

you

, but instead of geniuses you look like monsters. The news shows our genetic units with gangrene, their flesh rotting off, eyes milky white and blind, and most of the girls are crazy, drooling too much to even say a word.

Then

the public asks one question: how can we do this to human beings—to girls? People don’t see them as things, as tools; they see them as people like you and me, and now they think we’ve murdered children in the most horrific ways possible: with war and disease.”

The general paused to light his cigar, puffing until the end glowed and thick smoke coiled around his head, floating through the hologram. One of the scientists coughed.

Fuck him

, thought Urqhart, and he puffed a cloud in the man’s direction, wishing the scientist would die on the spot, enjoying, for a moment, the thought of drawing his pistol and firing into the man’s head to get everyone’s attention—to show this wasn’t an academic exercise.

The scientist who had spoken before nodded and folded his hands. “We think the problem lies in their psychological conditioning—while the girls are growing in the tanks. Apparently faith wasn’t the answer our psychiatrists assured us it would be.”

“Where are they now?” asked Urqhart, looking around the room. “Are there any shrinks here?”

The man shook his head. “No, General. We contracted psychiatric efforts to Hamilton Diversified, who refused to let their people attend this meeting without the company attorneys.”

“Typical.”

“But I spoke with one of their junior psychiatrists, a bright kid named Alderson, assigned to one of the deployed observation and maintenance teams. He had an interesting insight. Alderson thinks that experience plays a greater role in the girls’ emotional development than was previously modeled, and that the problem is one of contradiction. Somehow realities at the front undermine their belief in God and the afterlife—make them doubt faith is the answer. And we don’t know why.”

The general’s anger faded. Maybe he had misjudged this particular scientist; it wasn’t the answer he wanted, wasn’t a roadmap to a solution, but it was enough to seed an idea in Urqhart’s mind, a notion that made him shiver with a sense that one day he and every man in the room would wind up in hell.

“I think I know why.” His scientists turned their attention back to him and the general sensed in them a kind of skeptical amusement. “You people are idiots. Psychiatrists. Biologists. Fucking hell,” he shouted now, his teeth almost biting through the cigar, “

this is war!

I can’t

believe

I

can see the problem, and yet we pay you people millions each year to figure these things out for us. What the hell are we paying you for?

I shouldn’t have to fix this

.”

He paused, scanning the room slowly, enjoying the moment for what it was and noticing sweat had appeared on some of their foreheads as he pulled deeply at the cigar.

“General,” someone said, “what’s your idea?”

“None of you have been in combat. And yet here you are, psychologically programming these girls for a combat environment, using religion not to infuse a sense of faith and duty, but to make them fearless. They

know

that if they die in war they go straight to heaven. It’s a start, but here’s the problem: it doesn’t mesh. Down in the tunnels, once your friends start dying and the shit hits the fan, reality is a whole different thing from what these girls are being taught. Faith is a funny concept—either you have it or you don’t—and war tends to mess with whatever scrap of it you might have.”

He stubbed out the cigar on the scientists’ table, leaving a black mark on its lacquered surface. “So, for now we do nothing. I have to reassign Special Forces units to their new mission, hunting down your mistakes, but the second batch of girls, the newer models, is almost in position for our counterattack. In a few weeks we retake the mines and hold as best we can. In the meantime we wait.”

As he headed for the door, his aides holding it open, the scientist who had done most of the talking called after him.

“General, I’m lost. Wait for what?”

“The girls,” said General Urqhart. “They sense that

what they’re taught about faith is bullshit, that it all came from someone who doesn’t know war, a bunch of four-eyed eggheads with no balls to speak of and even less experience. We need them to learn from someone who speaks their language, one of their own, someone who’s seen the ass-end of humanity and still reported for discharge.

“So keep the psychiatrists in the field, conducting interviews, and assign this guy Alderson to watch the most promising girls, to look out for one that seems better than the rest. We’re looking for someone who can tell the story of faith and war in a way that rings true for all the others, and we’ll record every single thing she says about it, incorporate it into our future mental conditioning packages.

“We’re waiting for a genetically engineered saint. And more than that, we need what the Greeks used to call a Psychopomp.” Before anyone could ask he gritted his teeth and said,

“Look it up, assholes.”

And you will come upon a city cursed, and everything that festers in its midst will be as a disease; nothing will be worthy of pity, not insects, animals or even men

.M

ODERN

C

OMBAT

M

ANUAL

J

OSHUA

6:17

L

ive forever

. The thought lingered like an annoying dog, to which I had handed a few scraps.

I felt Megan’s fingers against my skin, and smelled the paste—breathed the fumes gratefully for it reminded me that I wouldn’t have to wear my helmet. Soon, but not now. The lessons taught this, described the first symptom of spoiling: When the helmet no longer felt safe, a sign of claustrophobia. As my troop train rumbled northward, I couldn’t tell if I shook from eagerness or from the railcar’s jolting, and gave up trying to distinguish between the two possibilities. It was not an

either-or

day; it was a day of simultaneity.

Deliver me from myself

, I prayed,

and help me to accept tomorrow’s end

.

Almost a hundred of my sisters filled the railcar, in a train consisting of three hundred carriages, each one packed with the same cargo. My newer sisters—replacements

with childlike faces—were of lesser importance. Megan counted for everything. She smiled as she stroked my forehead, which made me so drowsy that my eyes flickered shut with a memory, the image of an atelier, of a technician brushing fingers across my cheek as he cooed from outside the tank. I liked those memories. They weren’t like the ones acquired more recently, and once upon a time everything had been that way. Sterile. Days in the atelier had been clean and warm—not like this.

“Everything was so white then,” I said, “like a lily.”

Megan nodded and kissed me. “It was closer to perfect, not a hint of filth. Do not be angry today, Catherine. It’s counterproductive. Kill with detachment, with the greater plan.”

I closed my eyes and leaned forward so Megan could work more easily, and so she wouldn’t see my smile while smearing paste on my scalp, the thin layer of green thermal block that would dry into a latexlike coating, blocking my heat. The replacements all stared.

“Do you know what to expect in Uchkuduk?” one of them asked. “It’s my first time—the first time for most of us. They mustered us a month ago from the Winchester atelier, near West Virginia. How should we prepare?”

“It’s simple,” I said. “There’s one thing they don’t teach in the atelier:

Bleeznyetzi

.”

Several of them leaned closer.

“Bleeznyetzi?”

I nodded. “It’s Russian for twins.”

“You are an older version,” one said. “We speak multiple languages, including Russian and Kazakh, and we know the word.”