Read A Matter of Life and Death or Something Online

Authors: Ben Stephenson

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #FIC019000

A Matter of Life and Death or Something (6 page)

I took the little black tape recorder that Simon gave me for my birthday out of my backpack and put it on top of a book called

Basic Gardening.

“How professional!” said Mrs. Beckham when she saw my tape recorder.

I pushed RECORD.

“So, Mrs. Beckhamâ”

“Brenda.”

“So Brenda. What are you doing this evening?”

“Arthur, right?”

“Arthur Williams.”

“Well Arthur, I took the day off of work. I called in sick. I told them I was up to my neck in mucus and I might be back tomorrow. Really, I wanted to dig up my garden.”

“Spring fever,” I said cleverly.

She laughed. “Certainly!”

“Isn't it too early for that still?”

“Well maybe,” she said. “Who knows.”

I knew. The ground was probably still frozen solid. But that wasn't the point so I kept interviewing.

“Where is everybody else?”

“Sam's at work still. He works late. The kids are all moved out of course, well you know that. Yup, too many cowboys and not enough Indians, as they say.”

“Native Americans,” I said.

“Hmm?”

“It's âtoo many cowboys and not enough Native Americans.'”

“Oh yes, yes of course.”

“Also First Nations.”

My brain started to boggle itself. It was a good thing she was a good talker, because I was not a good interviewer. It was really hard to figure out what we were talking about, so I didn't even know which questions to ask. But she was kind of interviewing herself anyway.

“So, I've just had my fingers in all the pies this afternoonâcleaning the house, reading, doing this and that, well you can probably tell.”

I couldn't tell.

“âAnd I haven't even

got

to the garden yet! But you know, a stitch in time saves nine.”

I nodded.

“Umm, so what do you need all this stuff for?” I asked.

“Which stuff?”

“I mean, well, nevermind.”

I wanted to get the heck out of there. Mrs. Beckham had sat down on a chair across the table and across the fort made of stuff, and I peeped over the top, between a checkery shirt and the edge of a DVD case. She was giving me a funny look, like kind of serious. I didn't want to waste any more time.

“What I really wanted to talk about was this,” I said.

“Brass tacks.”

“What? No,” I said. I took the notebook from my backpack.

“What've you got there?”

“I found this book in the woods, and someone named Phil wrote it.”

“You think it's Phil's?”

“Well, I know it's Phil's,” I said. “It's got his name on it. And also everywhere inside it.” I held the book out way up high for her to have a look, but she didn't move her hand to take it from me, and she didn't even really look at it. She looked like she was thinking, like she was staring at something, and her eyes were moving backward and forward. My arm got a little sore of holding Phil in the air so I stopped reaching and slowly put Phil down in my lap. Mrs. Beckham's shiny lips were mumbling things under her breath.

“Five, four... well, it's probably only four or five there, right now,” she said. “I'll try him!”

She got up and rushed over to the phone, and then I realized what I hadn't been realizing yet. There was a person I'd entirely forgotten about, and he was Mrs. Beckham's son, and his name was Phil Beckham. Once, a long time ago, he babysat me. Just once.

“No, that's okay,” I said pretty loudly, “it's probably notâ”

“Oh don't worry about it,” she said, “I was going to call him today anyway.”

She dialled the numbers.

“You'll never

guess

where he lives now,” she said to me, as if she had something amazingly interesting to say. I didn't guess.

“

Phil

adelphia!”

She yelped out a bunch of laughs at herself, not seeming to care whether I found it very funny or not. I didn't, by the way. Then her laughter was cut off by a muffled sound in the top part of the phone.

“âPhil! Hello dear. How's

Phil

adelphia today?” She started laughing again, and miles and miles away, I bet Phil Beckham probably laughed too. I'd seen him laugh a couple times.

I put my head inside of my hands and bent down under the stack of laundry under a small piece of plywood under a round clock under a stack of books under my tape recorder, so that the wall came up really tall between me and Brenda. I laid my forehead down on the cover of Phil's book, rubbed my eyes and took a bunch of deep breaths.

On the tape, you can hear Brenda and the impostor Phil's conversation going on and on behind the wall of stuff for an entire twelve and a half minutes before you hear the loud roar sounds of the tape recorder being stuffed into my backpack. I decided to leave. I sat up in stealth mode and slipped Phil back into my backpack too, zipped the zipper and put it on my back. I sneaked my way out of the kitchen and into the living room while Brenda's back was turned to me. I stood in there and considered my next move. I could just barely see into the kitchen from where I was, and I could see the curly white phone cord wiggling around in the air, and tap tapping against the fridge.

A pile of jeans on the living room couch bulged up out of nowhere, and a poofy white cat silently hopped to the floor. It looked at me with its yellow eyes, and then strolled its way over to my feet. He or she seemed friendly enough, and actually started to wrap itself around my legs and go around and around between them, kind of in the shape of the symbol for infinity, which is called a “lemniscate.” While the cat was lemniscating I leaned down and got small, and I touched its smooth back and it shot up like a gigantic inchworm. I didn't really know that many cats. It sniffed my bare feet, and I felt a bit smelly, but I don't think it cared, because it started to sort of lick my toes. It licked my big toe, then the next, then the next, then all of them at once. It felt

exactly

like wet sandpaper.

I kind of giggled even though I wasn't in the mood to laugh, because it was really tickling. Brenda peeked out from the kitchen door, and looked at me, smiling, with the phone cord yanked out straight behind her.

“Oh Phil, I almost forgot! Little Arthurâyou remember Arthur Williams? No, yes. Yes exactly. He was wondering if you lost a book.”

The cat finished my toe bath and softly hurried up a few of the grey carpeted stairs to the second floor, and sat there watching me.

“No, a black and white notebook. What? Yes, black and whiteâspeckled. Yes. No? Okay, I would've figured as much. Yes. Would've figured as much.”

She put her hand over the bottom part of the phone and whispered, “He says it's not his,” and went back into the kitchen to keep phoning.

“Obviously,” I whispered to the cat.

I tiptoed down the hall and shoved my boots on and opened the door to outside. It was almost dark.

“Well, Phil, nice to talk to you. Just wanted to separate sheep from goats, you know, asâ”

I shut the door as softly as I could, tiptoed half of the driveway and then ran the rest. When I finally got to the street I slumped all the way back home, picking up twigs every once in a while and snapping them in half.

I got home and went past the kitchen and the room beside, where Simon was doing work on the computer, and I went to my room and opened my closet and stared at the bulletin board. I thought about Brenda, and the piles of stuff. I thought about the chocolate chip cookie, and the frozen garden. I thought about the whole stupid evening, and tried to think of something I might have learned. Years later, I wrote on another scrap of paper and tacked it up with the rest.

CLUES:

â From the bent tree you take five steps away from the river and one sideways towards the house.

â It must have been there a while.

â Because of the mud and water and rust.

â How you can't possibly think of anything else.

â It was in the woods.

â Someone named Phil.

â How the cat's tongue felt

exactly

like wet sandpaper.

THEY BUILD it together. We see another man, a man with glasses and slim limbs, a man carrying on his square shoulder a young boy, kicking squirming laughing. He always carries the boy this way, at least every time we see them come to build: he holds the boy's waist and flings him up onto his shoulder and they walk among us. The man places his steps with visible caution: he is walking for two. With his other hand, on the non-boy side, he carries a red toolbox. When they get to the spot, the man bows and the boy's small feet touch the ground as the toolbox's scuffed bottom does the same.

Though the man does the bulk of the work, he makes sure the boy always has some task, some skill to contribute: see him pass the box of nails to the man when he asks. See the boy holding the level, the man asking if the bubble is centred, the boy checking and screaming yes. The boy sitting with his back to the man, stacking small towers of dusty scraps of wood, humming structureless wandering songs that he invents as he goes.

The man places the boards of the ragged frame and the plywood to clothe it. The wood they use is from a pile of leftovers from the building of their house, years ago. The man starts the nails with his hammer, leaving an inch for the boy to finish with his own boy-sized hammer. Often the boy bends a nail in half, and the man starts another one just beside. Sometimes the boy demands to use the big hammer, making the man use the small one instead.

Between three of us, a small triangular floor soon sits. A moment later, a top floor as well. Then two ladders, one for each level, and a roof: a wavy bit of mint-green fibreglass blazing translucent in sunlight. The man watches the boy climb the ladder to the top floor for the first time.

The whole treehouse is a “house” in fashion only. This is no shelter, no residence. It provides for no physical need. But in the moments to come, it transforms from fort to castle to clinic to airship to hotel to laboratory to lifeboat. To the boy running climbing stomping and yelling, to the boy growing, it is anything.

We don't mind this, this use. As much as they confuse us, we trust the humans. What reason would they have to let us go to waste? They can sense our value, in some way they must feel it. However, one thing we do find confusing. Sometimes after we are cut, they will count the rings exposed on our cross-sections. They count our layers, and this counting seems somehow important. Is it a game? “This one is fifty years old,” they say. “This one is almost a hundred.” Is it a joke? Surely they know that we, who have seen nearly every age, who have been here for so long, passing our vision through time in all directions, we who live in all time as in a single momentâsurely we are not

years old.

Why do they want the rings' number? Do they even notice their shape?

Now the man and boy return; again they are building. The boy is taller and needs a bigger palace.

The two builders drive a circuit of the neighbourhood, searching for supplies in roadside junk piles. It is “spring cleaning.” They collect as many building blocks as will fit into their car and they return home.

They are adding and climbing and reimagining. This addition will be several times larger than the first; in a sense it will make the original an annex. Like its tinier parent, it also gets two floors, built of varied length two-by-four and other scrap beams. Inside, a ladder leads from top floor to bottom, then a set of stairs connects the bottom to the soft leafy earth.

See them stitch its walls together like wooden quilts, like pages of a wooden scrapbook, tightly sewing in all their neighbours' discarded window frames, their rusted screens with holes punched through, a gunrack that will never again hold a gun, sturdy railings draped with stiff wire mesh, a small family of shingles, a burgundy paint-peeled door. See them top it with a half tin, half mint-fibreglass roof.

The man places a four-foot piece of ply between each of the first floors connecting old to new, the boy nails the bridge down and the treehouse becomes a whole. They sit in the top floor eating ham and cheese sandwiches, swatting mosquitoes and watching the river.

The boy darts around in the treehouse's crow's nest. It pours. His ship has taken in too much water. He bails it over the railing with an orange bucket.

He stands on the bottom floor's stage; it's a hot afternoon. He's narrating his first one-man play, about a boulder who wishes it were an acorn. It's opening night and a chipmunk watches, apparently captivated.

He balances on the outside of the wall, with his stomach and spread arms pressed against it. His feet perch on whatever jutting beam or convenient branch might support his weight, exactly as the man had made him promise never to do. But he is inching along one final rock face and he is so close to the summit.

Then he is not here. When the book falls and the man walks to the water, the boy is not in the treehouse. It sits empty. We still see the boy, and he is often near us, but the boards of the treehouse hover virtually untouched. Now they've weathered so much rain and snow and wind that they match the colour of our skin. The shrine's mossy wood blends seamlessly into our bark and we embrace it. The boy still leaves it alone. Should someone come and pull out every one of its nails, we know the treehouse will still float here, fused to us.

ALONE

ONLY

HEART

HER

I haven't written in days. I was feeling quite a bit better for a while there but now today it's hopeless. I've literally been pacing down the hall for like an hour. Lost. Can't sort out the tasks involved in making anything more than cereal, and so I eat cereal for breakfast lunch supper, this whole week so far. I thought about making a sandwich today and just stared into the fridge. Can't even begin to expect anything of today. It's making me so fucking antsy to write! Not calming at all! I feel pulled in so many directions and like there's all this stuff I should be doingâcan't do any of itâgive it up.

And half the time I wake up and almost call her. My mind accepts no order. Chronological least of all. Things don't happen chronologically to meâthey never did. Things never “did,” and then “do,” and then “will.” They would and then they do and then they will and did. They mix themselves around even while happening, and once they become memory it's even more helpless. As far as I can see, everything in my life happened at once.

AND > THERE'S > NOTHING > LIKE > THIS,

MORE

IT'SÂ Â Â Â Â ALWAYSÂ Â Â Â Â MUCH

THIS.

Â

USUALLY

LIKE

When someone tells me a story in which some events happen to them in some kind of time-based order, I assume they're either lying or insane. If someone wrote my biography (not that they would or should) I'd make them play fifty-two pick-up with the final draft.

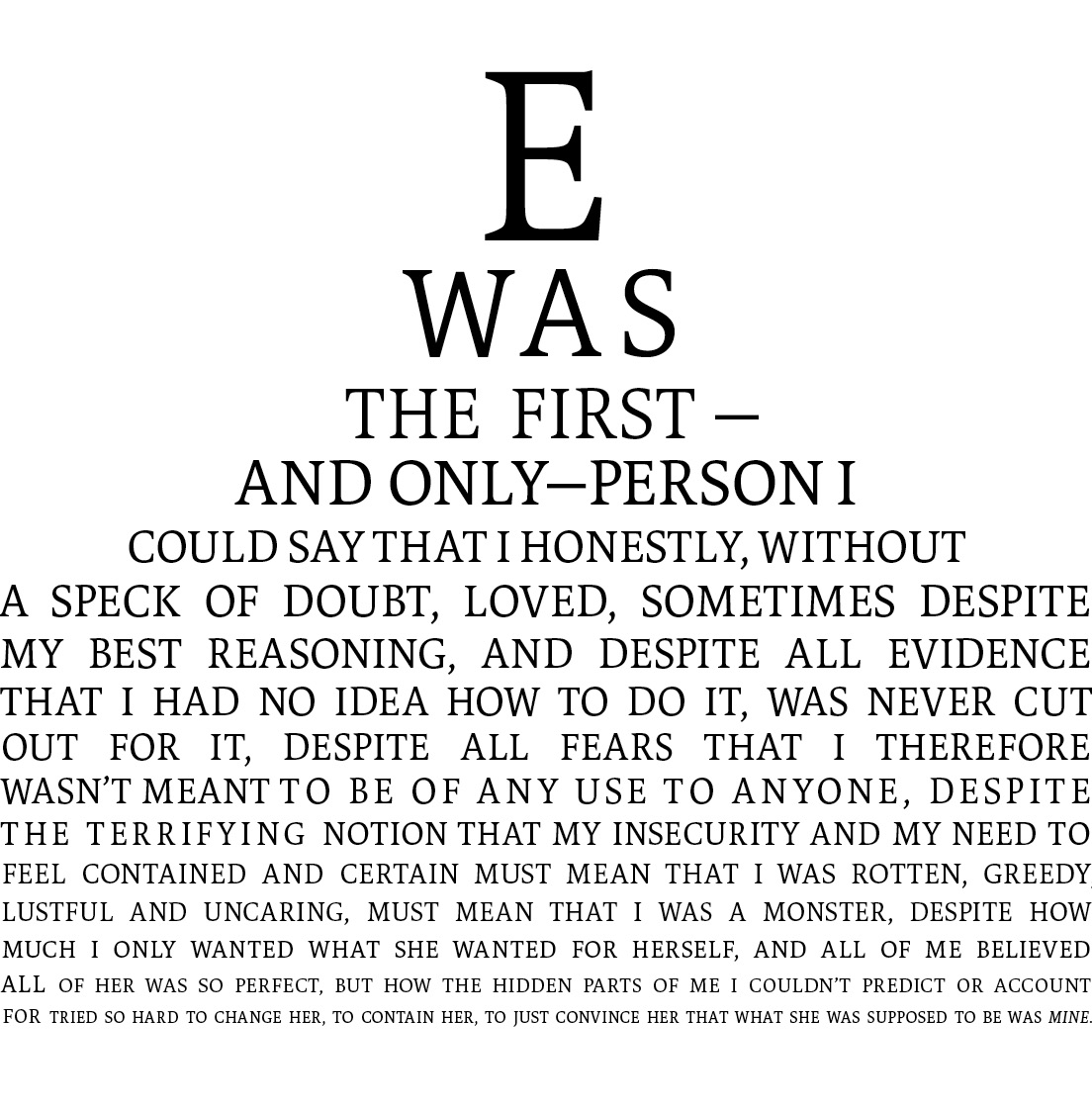

FIRSTLY, (as if anything else ever happened to me) let's begin with E. Yes, we'll just leave it at “E,” upper-case E, like an eye-test chart. Which was one of the many things she was, to put it horribly. To put it horribly, there were some parts of her that I always had to squint at and still couldn't read.

And if I can just get it all downâbig and smallâthen it's mine. And it's

over,

and I can stop. I can't bring any of it back. I can't summon you, but at least I'll have tried.

We met in our last year of school. We were both trying to finish. There was no dramatic story about our meeting, we were just in the same class. You just walked around the studios like you were lost but wouldn't have had it any other way. You would later say that I walked around like a puppy whose leash was “too slow.” Eventually I talked to you, and after a few days of the first talks I was shocked because we actually

were

talking: we were talking about actual things. We were agreeing and disagreeing, we were arguing and laughing, we were spending eight hours together, we were plotting.

I fell for you so hard that all I could do was worry about falling for youâabout turning you into something you weren't, some muse or divine icon, so I vowed not to, but then I couldn't imagine how I might dream up anything better than the full, actual you. You made me think thoughts that dangerous.

You were someone so dangerously close to the person I'd always (subconsciously) dreamed of meeting that you caused me to (consciously) adjust the idea of that person, to completely discard it, because you'd trumped it. You could tell, couldn't you?

You were beautiful, and not in a way where I noticed things about you that were beautiful and could point them outâI could do this, and I did, but it never seemed to have much to do with the true youâyou were beautiful in a way that was its whole own thing, you seemed a completeâsomethingâand whatever you were I knew I didn't want to change one thing about it. I wasn't exaggerating.

Sometimes you were peppy and confused and honest and shrugged your shoulders and laughed and said Oh Well to the world. Other times the world weighed down on you tremendously for weeks at a time, and I did all I could to make it easier, but all I could do was not much.

When you spoke, you said things without the slang you were supposed to use, and in tones of voices I'd never heard, only imagined. Your sentences were unpredictable. Sometimes you would actually sing them, and I didn't know what to do except laugh. You were funny. You didn't think anyone got your jokes. I'm not convinced anyone didâno one could have been ready for you. Sometimes you would pause in the middle of a sentence and then switch to something extraneous that at first glance didn't seem to complete the initial thought, but to someone who knew you, you made sense in some hilarious and abstract way that went beyond language. You made something better than “sense.”

I thought I understood that I would never understand you, but then maybe I secretly thought I understood you.

You understood me. You put me back inside myself. You made me think I was OK, like I was normal. (Like I was nowhere near normal and that was fine.) Like I was

good.

Remember? I couldn't explain myself to you, but then I didn't have to explain. I wanted to be like one of your thoughts, like one of those unexpectedly and vaguely completed things. You finished my sentences in ways I myself never could have. You came from some other reality with such detail and integrity that it terrified me. You terrified me. I loved you. (Remember?) You loved me too, somehow, and of course I didn't know why at first, but gradually I did. Maybe I didn't believe it at first, but does anyone? Maybe you helped me see things that had always been there. Things like me. When we were together, I reminded me of myself. And you were yourself, and who else was there? Maybe there were no secrets anymore. Why would there be? Maybe we lived in a world totally without secrets, and perhaps we couldn't imagine living in any other. Maybe I only wanted what I already had.

(And maybe you didn't need me.)