Black Genesis (2 page)

1

STRANGE STONES

In Nabta there are six megalithic alignments extending across the sediments of the playa. . . . Like the spokes on a wheel, each alignment radiates outwards from a complex structure. . . .

D

R

. M

OSALAM

S

HALTOUT

, N

ATIONAL

R

ESEARCH

I

NSTITUTE OF

A

STRONOMY AND

G

EOPHYSICS

, E

GYPT

[One of the] alignments points to the rising position of Sirius . . . the primary calibrator of the Egyptian calendar. . . .

D

R

. F

RED

W

ENDORF AND

D

R

. R

OMUALD

S

CHILD

,

T

HE

M

EGALITHS OF

N

ABTA

P

LAYA

A LUCKY TURN OF THE SPADE

The phrase

a lucky turn of the spade

is well known in archaeology. It reminds us that many of the great discoveries have often been made not by intellectual ingenuity, as we would expect, but by pure chance. Moreover, it implies that the credit does not necessarily always go to the person who actually held the spade, but rather to his employer, the leader or financier of the archaeological project. For example, when, in 1873, a Turkish worker plunged his rusty spade into the soil and discovered the legendary city of Troy, this was a lucky turn of the spadeânot for himâbut rather for the German adventurer Heinrich Schliemann. When, in 1922, an Egyptian peasant shifted the sand with his spade and discovered the entrance to Tutankhamun's tomb, this too was a lucky turn of the spade not for him but for the English archaeologist Howard Carter. Schliemann and Carter became legends in their own time; the workers were given a small stipend and then departed into oblivion.

So when an unnamed student from Southern Methodist University of Texas (SMU) discovered Nabta Playa, his or her name was somehow lost and forgotten in the academic verbiage that followed. Admittedly, this time there was no lucky turn of the spade. In fact, there was no spade in the hand of the unnamed student. The leader of the expedition, Fred Wendorf, and the student as well as a few others with them had by chance stopped their Jeep in order to have a comfort breakâa peeâafter a long and tiring drive in the Egyptian Sahara. They were 100 kilometers (about 62 miles) due west of Abu Simbel in a nondescript, empty desert spot. During their rest, as they looked down around their feet, they slowly realized they were standing in a field of numerous artifacts, the remnants of finely made stone tools and potsherds. Those artifacts alone were intriguing enough to prompt Fred Wendorf to investigate further and begin an entirely new excavation site. What the explorers did not then realize was that the strange clusters of large stones all around them, half-buried in the sand, would eventually shock the world's concept of antiquity. At first the members of the expedition assumed that these stones were just natural boulders sticking out of the ancient sedimentâa common feature in this arid part of the world. In fact, for years, as they excavated in the midst of the boulders, searching for and finding the expected Neolithic artifacts, they assumed the large stones were natural bedrock outcrops. As they looked closer, however, it dawned on them that the stones were positioned in unnatural formationsâstrange geometrical clusters, ovals, circles, and straight linesâand they were sitting on the sediments of an ancient dry lake. Someone had taken the trouble to move these stones at great effort. Who had done this? When? More intriguingly, why? It would be no exaggeration to say from the outset of our story that Wendorf's findings and those of his team, which were published gradually from the mid-1970s until very recently, should have shaken to its very core the scholarly world and should have changed its perception of Egyptian history and even, perhaps, of civilization as a whole. This, however, didn't happen. Nabta Playa and its mysteries remained an undefused intellectual bomb, ticking away, remaining unexploded in the hallways of established knowledge.

Until now.

THE COMBINED PREHISTORIC EXPEDITION (CPE)

Fred Wendorf's fascination with the Egyptian Sahara started way back in 1960, when, in a desperate bid to save Egypt's ravaged economy, the Egyptian government decided to build a huge dam on the Nile just south of Aswan, 900 kilometers (about 600 miles) from Cairo. Egypt's population had burgeoned from a comfortable ten million at the turn of the nineteenth century to an unsustainable fifty million by 1960, and the country was now in dire need of cheap energy to service the ever-growing masses and sprouting agricultural and industrial projects. There were also new infrastructure projects planned for the delta region and all along the 1,000-kilometer (about 621 miles) Nile Valleyâroads, pipelines, sewage plants, airports, hospitals, and schoolsâwhich President Gamal Abdel Nasser had promised the people after the so-called Free Officers Revolution of 1952. Unable to obtain funds for all this from the Western powers because of ongoing anti-Semitism in Egypt and the country's hostilities with Israel, Nasser was forced to seek help from communist Russia, which was eager to introduce socialism to Egypt and to gain a foothold in the Arab world. For infrastructure projects Egypt provided cheap labor from its huge unemployed masses, while Russia provided the cash and the technologyâand even threw a few Mig jet fighters and tanks into the deal.

When finished, the dam on the Nile was to form a giant lake, Lake Nasser, which not only would flood much of the inhabited Nile Valley upstream but also would submerge many ancient temples, among them the great temple of Ramses II at Abu Simbel and the beautiful temple of Isis on the Island of Philae. The archaeological world communities were outraged. Not as well publicized at the time, but also slated to be lost were several prehistoric sites in the adjacent desert earmarked for new farming projects. At the eleventh hour, however, UNESCO World Heritage sounded the alarm, and funds were quickly raised from big donors across the world. A huge international rescue operation hastily worked to save the ancient temples. The effort involved experts and engineering contractors from Europe and the United States.

Yet while this sensational salvage operation grabbed all the headlines, another, more modest, operation went relatively unnoticed. This was the scantily funded rescue mission started in 1962 and headed by Fred Wendorf, who was then curator of the Museum of New Mexico. Fred Wendorf had set himself the daunting task of salvaging or, at the very least, documenting in detail the prehistoric sites in the Egyptian Sahara before they were lost forever. Wendorf 's rescue operation was at first funded by the National Science Foundation of America and the U.S. State Department and was made up of an informal team of anthropologists, archaeologists, and other scientists who were given the collective name of Combined Prehistoric Expedition, or CPE. Three institutions formed the core body of the CPE: SMU, the Polish Academy of Sciences (PAS), and the Geological Survey of Egypt (GSE). In view of his credentials and seniority, Wendorf remained in charge of the CPE. In 1964 Wendorf resigned from his post at the Museum of New Mexico and joined Southern Methodist University (SMU) as head of the anthropological departmentâa move that allowed him to devote more time to the ongoing research in the Egyptian Sahara. In 1972, however, Wendorf handed the day-to-day operations to a Polish anthropologist, Dr. Romuald Schild. At this point, both Wendorf and Schild admitted, “Only a few signs suggested that a new archaeological dreamland is there buried in the sands

and clays.”

1

Barely a year later, however, in 1973, after Wendorf 's fateful pee break 100 kilometers from Abu Simbel, and after they walked around the large, shallow basin and saw all the strange stone clusters and protracted alignments as well as a plethora of tumuli and potsherds strewn all over the ground, both men started to suspect that just maybe they had hit the anthropological jackpotâfor this was no ordinary prehistoric site. It was a sort of unique Stone Age theme park in which mysterious events and occult ceremonies quite obviously took place. The local modern Bedouins called the region Nabta, which apparently meant “seeds.” Borrowing this name and concluding that the wide, sandy-clay basin they stood on in the desert was the bottom of a very ancient lake, Wendorf and Schild christened the site Nabta Playa.

But what exactly is Nabta Playa, and what are the mysteries it conceals?

CIRCLE, ALIGNMENTS, AND TUMULI

The Egyptian Saharaâwhich is also known as the Eastern Sahara or Western Desertâis a vast, rectangular region that is bracketed on its four sides by the Mediterranean Sea in the north, the Nile Valley in the east, Libya in the west, and Sudan in the south. It is almost the size of France, and, apart from the five main fertile oases that run in a line from north to south, it is considered the most arid and desolate place in the world, especially the corner in the southwest, adjacent to Sudan and Libya. Because of this terrible aridity and also because some parts of it are so remote, the Egyptian Sahara remains largely unexplored. True, some archaeological research has taken place in and around the five major oases, but few, if any, explorations have been carried out in the deep desert or in that distant southwestern corner. This is especially the case for the two highland regions known as Gilf Kebir and Jebel Uwainat. These are composed of giant, rocky massifs that act as a natural barrier to Egypt's southwest frontier corner with Sudan and Libya. These almost surreal “Alps of the desert” emerge from the surrounding flat landscape like giant icebergs in a still ocean, and in daytime they loom in the haze like eerie mirages that can taunt, daunt, and terrify the most intrepid or placid of travelers.

As odd as it may seem, especially given our perspective of today's amazing technological advances in communication, no one in modern times knew of the existence of Gilf Kebir or Jebel Uwainat until the early 1920sâor so it seemed, as we will see in chapter 2. The abnormally belated discovery of Gilf Kebir and Jebel Uwainat coupled with their remoteness and the harsh and extremely inhospitable climate of the region are the main reasons for the almost nonexistent archaeological exploration there. In addition, there has been a strange disinterest by Egyptologists who have insisted that it was impossible for the ancient Egyptians of the Nile Valley to have reached these faraway places through vast distances of open and waterless desert. Nonetheless, this belief is somewhat odd, because it has been known since 1923 that Gilf Kebir and Jebel Uwainat were once inhabited by a prehistoric people who left evidence of their presence there in an abundance of rock art on ledges and in caves and in the many

wadis

(valleys) skirting the massifs. Perhaps the greatest mystery of these strange places was that, in spite of the plentiful rock art and stone artifacts that attest to human presence, no actual human remains or even empty tombs have so far been found there. This was also the case at Nabta Playa.

The question surely begs asking: Were Gilf Kebir, Jebel Uwainat, and Nabta Playa not places of permanent habitation but outposts for people who moved from place to place and who had their home base elsewhere? For example, could the people of Nabta Playa, with their mysterious megalithic legacy, be the same people of Gilf Kebir and Jebel Uwainat, with their puzzling rock art legacy? If so, then how could such people traveling on footâor, at best, on donkeyâacross such vast distances (there are 580 kilometersâabout 360 milesâbetween Nabta Playa and the Gilf KebirâJebel Uwainat regions) in this totally waterless desert?

Before we attempt to answer such questions, we must look at an interesting and possibly very relevant geographical fact: Nabta Playa and the Gilf KebirâJebel Uwainat area are almost on the same eastâwest line that runs just north of latitude 22.5 degrees north, forming a sort of natural highway between the Nile Valley, Nabta Playa, and, at its western end, Gilf Kebir and Jebel Uwainat. From a directional viewpoint, then, ancient travelers would easily have known how to journey to such distant locations simply by moving due east or due westâa direction that can be determined by the sun's shadow. Knowing, however, in which direction to move is one thing; making the long journey to an end point is quite another. Such a long stretch of desert crossing is impossible on foot or on a donkey unless there are watering holes or wells along the way. Yet there are no wells or surface water in this stretch of desert between Nabta Playa and Gilf Kebir, only bone-dry sand, dust, and rocks. Nothing can survive in this wasteland without adequate sources of water. Indeed, that Jebel Uwainat and Gilf Kebir were discovered so late shows how problematic it is to reach these regions without motorized four-wheel-drive vehicles that are fully equipped for rough terrain.

Because of this, as well as the hazards involved in such deep desert trekking, only a handful of people have ventured into this wilderness. The region is still a no-man's-land for tourists, and very few, if any, Bedouins who roam the Egyptian Sahara go there. In fact, so uninterested were Egyptologists in these remote areas that the places wereâand still areâhardly mentioned in any but the rarest of Egyptological textbooks. Oddly enough, in 1996 it was left to Hollywood to generate some interest in Gilf Kebir and Jebel Uwainat through the academy-awardwinning film

The English Patient

in which the hero supposedly crashes his single-engine plane on the western side of Gilf Kebir. Yet even then the scenes in the movie were shot not on location but in the more accessible desert of Morocco.

*1

At any rate, whatever the reason, Gilf Kebir and Jebel Uwainat were not included in the Combined Prehistoric Expedition mandate. The CPE must have assumed, as most Egyptologists did in those days, that no one could have traveled such vast distances in the arid desert in ancient times, and, therefore, there could not be a direct connection between the prehistoric people of Gilf Kebir and Jebel Uwainat and the people who built and occupied Nabta Playa. We will return to this important misjudgment in the next chapter.

In the later twentieth century another misjudgment occurred: although from 1973 to 1994 the site of Nabta Playa was the intense focus of anthropological and archaeological investigations by the CPE, it nonetheless failed to take notice of the very obvious megalithic alignments there, and it certainly did not have them checked by an astronomer. This was a rather curious oversight that even Fred Wendorf himself had trouble explaining: “The megaliths of Nabta were not recognized or identified for a long time. We began to realize their significance only in

1992. . . .”

2

and “it is not clear why we failed to recognize them previously, or rather why we failed to understand their significance during the first three field seasons 1974, 1975, and 1977 at Nabta. It was not that we did not see them because we did, but they were either regarded as bedrock or, in some instances where it was clear they were not bedrock, regarded as

insignificant.”

3

As the author John Anthony West once remarked, archaeologists can have blindered views and miss the obvious: “[I]f you are bent on looking only for potatoes in a field of diamonds, you will miss seeing the

diamonds!”

4

To be fair to the CPE, though, the anthropo logical and archaeological evidence so far was in itself exciting stuff. Carbon-14 dating resulted in dates as far back as 7000 BCE and as recent as 3400 BCE, showing an on-and-off presence at Nabta Playa over an incredible span of years: more than three and a half millennia. The evidence at Nabta Playa also showed that at first, people came seasonally, when the lake was filled by the monsoon summer rains, arriving probably in July and staying until January, when the lake dried up again. Eventually, sometime around 6500 BCE, they figured out how to stay at Nabta Playa permanently by digging deep wells. Around 3300 BCE, however, the changes in climate made the region extremely arid, and Nabta Playa had to be abandoned. The mysterious people simply vanished, leaving behind their ceremonial complex that the CPE had discovered more than five millennia later. Its members were now at odds to understand the function and meaning of the complex.

First the CPE was baffled by the dozen or so oval-shaped tumuli at the north side of Nabta Playa. These looked like flattened igloos made of rock debris and covered with flat slabs of stones. More baffling still was when one of these tumuli was excavated by the CPE. It was found to contain the complete skeletal remains of a young cow, and other tumuli also contained scattered bones of cattle. Wendorf christened the area “the wadi of sacrifices” and concluded that these cattle burials and offerings appear to indicate the presence of a cattle cult. Radiocarbon dating placed these cow burials at around 5500 BCE, thus at least two thousand years before the emergence of the well-known cattle cults of ancient Egypt, such as those of the cow-faced goddess Hathor, the universally known goddess Isis, and the sky goddess

Nut.

5

There were also strange clusters of large stones at the western part of Nabta Playaâabout thirty of them, which the CPE called complex structures. When some of these were excavated the CPE found, to its great astonishment, that these structures had been deliberately placed over natural rock outcrops that were 3 to 5 meters (about 10 to 16 feet) below the surface of the earth. Furthermore, it seemed that these strange rock outcrops had actually been smoothed to “mushroom-like” shapes by human hands! The largest of these so-called complex structures was named Complex Structure A (CSA). When excavated it was found to contain, at a depth of 3 meters, a large, rough stone sculpture carved to look something like a cow and placed above the sculpted rock outcrop. Moreover, emanating from Complex Structure A were a series of stone alignments that shot out like spokes from a bicycle wheel for several hundred meters, with some projecting toward the north and others toward the east.

Figure 1.1. Prehistoric palette found at Gerzeh, ca. 4000â3000 BCE, thought to represent the goddess Hathor.

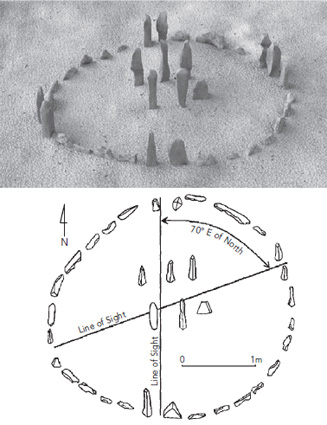

There was more, however. The now-famous part of Nabta Playa, its pièce de résistance, was a small stone circle at the northwest part of the site, which looked a bit like a mini Stonehenge. The standing stonesâtwenty-nine of themâthat formed the circle contained four gates, which created lines of sight that ran eastâwest and northâsouth. Placed in the center of the circle were two rows of three upright stones each (six stones in total), which gave the whole arrangement the appearance of the dial of a giant clock. Some of the stones had clearly been displaced, perhaps by vandals, and so the CPE invited a young and gifted anthropologist from the University of Arizona, Dr. Nieves Zedeño, to help them reconstruct the circle to its original form of millennia ago. Clearly this was no ordinary prehistoric structure. At this stage the CPE anthropologists were completely baffled as to what purpose it might have served. Wendorf and Schild were now beginning to suspect that the whole of Nabta Playa might have less to do with anthropology and more to do with astronomy. So, in 1997, they finally sought the help of an astronomer from the University of Colorado in Boulder, Dr. Kim Malville, who was known for his specialized studies on the astronomy of prehistoric sites. They were in for a big surprise.

Figure 1.2. Schild with Calendar Circle, Nabta Playa, winter 1999

Figure 1.3. Artist's graphic depiction of the Calendar Circle, based on the archaelogical reconstruction map of Applegate and Zedeño. Graphics by Doug Thompson for Carmen Boulter.