Book of Fire (32 page)

In Antwerp, Tyndale rejoiced too, his words for once matching

More’s in crudeness. The cardinal had died a ‘shitten death’, he wrote, having collapsed after his physician gave him a purgative, and it was now, as we have seen, that Tyndale revelled that ‘for al the worship of his [cardinal’s] hat and glories of his precious shoes when he was payned with the colicke of an evel conscience havynge no nother shifte bycause his soule could funde in nother issue toke hym selfe a medecine

ut emitteret spiritum per posteriora

’.

A sea change was beginning for the reformers. Thomas Cromwell, by now the king’s secretary, was the main influence, and it was he who instigated and took in hand the approach to Tyndale. One of the most far-sighted and brutal of Tudor administrators, Cromwell was a meticulous organiser with a contrary streak as adventurer and fortune-hunter. He was born at Putney, three miles upriver from More’s great Thames-side house at Chelsea. He was a barrel of a man, with a strong jowl and close-set hawkish eyes. His father was variously described as a brewer, a fuller or a blacksmith. At nineteen, an age when Tyndale, and More and Wolsey, were refining their intellects at Oxford, Cromwell crossed the Channel to seek his fortune as a mercenary. He followed the French armies in Italy for eight years, also gaining book-keeping expertise as a clerk and business acumen as a trader.

He came back to England in his late twenties, setting himself up as a wool stapler, a dealer in raw wool. He married an heiress, and learnt some law, working as a scrivener, drawing up contracts and money-lending. After a year in London, he entered Wolsey’s service. The cardinal was a good judge of men, and he recognised Cromwell’s tenacity and ambition. By 1525, Cromwell was a Member of Parliament and Wolsey’s dogsbody, supervising the endowment of the impressive new colleges Wolsey was founding at Ipswich and Oxford.

He stayed loyal to his master longer than most, and feared he would go down with the wreckage. Wolsey’s gentleman usher and

biographer, George Cavendish, came across Cromwell reciting prayers to the Virgin and weeping. It was ‘a very strange sight’ to find so hard a man in such a state, and Cavendish asked him if he was distressed for the cardinal, who had been forced to resign a short time before. ‘Nay, nay,’ Cromwell said, ‘it is my unhappy adventure, which am like to lose all that I have travailed for all the days of my life for doing of my master true and diligent service.’ He was weeping for himself, and for his ruined prospects. Typically, however, he had a plan to take his fate by the scruff of the neck. ‘I do intend, God willing, this afternoon … to ride to London and so to the court,’ he told Cavendish, ‘where I will either make or mar or I come again … I will put myself in the press to see what any man is able to lay to my charge of untruth or misdemeanour.’

Thomas Cromwell exercised immense influence as principal royal secretary after the fall of Wolsey and More. Though an earl when Henry VIII tired of him and had him beheaded, Cromwell was the son of a Putney brewer and blacksmith, and a radical who sympathised with Tyndale and tried to reconcile him with the king. His efforts foundered on Tyndale’s refusal to pay lip service to the royal position on the divorce and the eucharist.

(Popperfoto)

Come again he did. He was too guileful, too competent and hard-working for the king to ignore. By the end of 1530 he was an influential member of the king’s council. Though devious, a man who turned on old allies and drew blood when it suited, he was sympathetic to the reformers. It was in his interests to be so, for he was able to use Henry’s fury with the pope to his own advantage, pressing the king to break with Rome, and making himself an indispensable part of the new doctrine of royal supremacy.

His views were close to those of Marsiglio of Padua, whose great work

Defensor Pacis

Cromwell paid to have translated into English for the first time. Marsiglio, a rector of the university of Paris, had argued against the temporal power of the pope and the clergy. He held the Church to be inferior to the State, which he saw as the power house and unifier of society. Clerics should have no privileges, he said, for ‘all Christ’s faithful are churchmen’. Marsiglio had been excommunicated for his pains in 1327. His ideas, though two centuries old by then, seemed raw and radical when Cromwell expressed them in terms of an English empire ‘governed by one Supreme Head and King’ to whom both

temporality and spirituality ‘be bounden and owe to bear, next to God, a natural and humble obedience’. Within three years, Cromwell himself was to become principal secretary with control of a range of affairs unmatched in the history of the realm. His leaning towards reform was personal as well as political. He was ultimately to be beheaded as an earl, but he had been born into the class of petty traders that was the breeding ground of Lollardy, and from which Tyndale drew his support. In religion, at least, Cromwell retained some of the adventure and free spirit of his youth. He was a natural ally of Tyndale.

Towards the end of November 1530, Cromwell sent an experienced merchant venturer named Stephen Vaughan to the Continent on a most secret and delicate mission. Vaughan was the king’s agent, a sort of commercial consul, in the Low Countries. He was instructed to find Tyndale, and offer him a safe conduct back to England. Vaughan sent letters to Tyndale in Frankfurt, Hamburg and Marburg – ‘Frankforde, Hanboroughe and Marleborughe’ – the three cities where rumour located Tyndale. The exile was offered ‘whatsoever surety he would reasonably desire for his safe coming in and going out’ of the realm.

On 26 January 1531, Vaughan wrote to the king that, although he had not found Tyndale, he had received a reply to his letters ‘written in his own hand’. Tyndale had refused the offer because he had heard the ‘bruit and fame’ of events in England, presumably the persecutions let loose by More and Stokesley, and suspected ‘a trap to bring him into peril’. Vaughan found out that Tyndale had written

An Answer unto Sir Thomas More’s Dialogue.

He did not know whether it had yet been printed, but assured the king that, ‘as soon as it is, I will send it without fail’.

Vaughan succeeded in tracking down a manuscript copy of the new book in March. He wrote to Cromwell on 25 March from Antwerp to say that the copy was ‘so rudely scribbled’ that he was

writing it out again in a ‘fair book’ to send to the king. Vaughan was uncertain whether Henry would like the

Answer

or not. ‘I promise you,’ he told Cromwell, ‘he maketh my lord chancellor such an answer as I am loth to praise or dispraise.’ He said that Tyndale had never written ‘in so gentle a style’ – a claim the clergy might have disputed, since Tyndale wrote of their ‘dumb blessings, dumb absolutions, their dumb pattering, and howling, their dumb strange holy gestures, with all their dumb disguisings, their satisfactions and justifyings’ – and that, if Tyndale heard that the king took the book well, it ‘may then peradventure be a means to bring him to England’. Other than that, Vaughan admitted, it was unlikely that he would come, ‘for as much as the man hath me greatly suspected’.

Then, remarkably, Tyndale broke cover. Vaughan wrote to Henry again on 18 April 1531. ‘The day before the date hereof,’ he said, ‘I spake with Tyndale without the town of Antwerp.’ A messenger had come to him, he reported, saying that a friend of Vaughan wished to speak to him. The messenger did not know the name of the friend, but said he would take Vaughan to him. Vaughan followed him to a field on the outskirts of Antwerp beyond the city gates.

A man arrived. ‘Do you not know me?’ he asked. ‘My name is Tyndale.’

‘But Tyndale!’ Vaughan exclaimed. ‘Fortunate be our meeting.’

‘Sir,’ said Tyndale, ‘I have been exceeding desirous to speak with you.’

‘And I with you.’

Tyndale said that he was upset and surprised that the king had disliked

Prelates

, ‘considering that in it I did but warn his grace of the subtle demeanour of the clergy of his realm towards his person, and of the shameful abusions by them practised, not a little threatening the displeasure of his grace and weal of his realm: in which doing I showed and declared the heart of a true subject …’. He

said that he had suffered greatly for his work, through ‘my poverty … mine exile out of my natural country, and bitter absence from my friends … my hunger, my thirst, my cold, the great danger wherewith I am everywhere encompassed’. He had warned the king to beware of Wolsey and the churchmen. How could the king feel that this did not show ‘a pure mind, a true and incorrupt zeal and affection to his grace? … Doth this deserve hatred?’ Tyndale went on to ask how Henry, as a Christian prince, could ‘be so unkind to God’ as to ‘dare say that it is not lawful’ for his people to have the scriptures in their own tongue. God had commanded that his word be spread throughout the world, to

give ‘more faith to the wicked persuasions of men’. Why were the king’s subjects so dangerous that they were denied that word in a language they could understand?

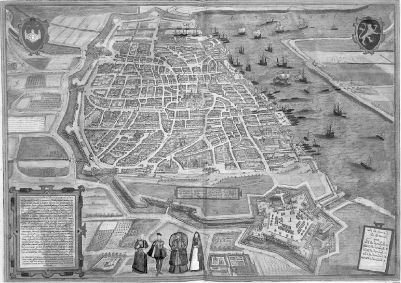

This map of Antwerp shows the waterfront, where smuggled copies of Tyndale’s works began their journey to England, and the walls of the great city. When Tyndale agreed to meet Stephen Vaughan, Cromwell’s agent, he was careful to do so in a field outside the gates. He then scurried off along a road leading away from Antwerp, so that Vaughan could not follow to him to his secret lodgings. Such vigilance kept him alive; only once, fatally, did he drop his guard.

(Bridgeman Art Library)

After a long conversation, during which Tyndale confirmed that he had finished his answer to More’s

Dialogue

, Vaughan ‘assayed with gentle persuasion’ to have him travel to England. ‘But to this he answered,’ Vaughan reported, ‘that he neither would nor durst come into England, albeit your grace would promise him never so much the surety: fearing lest, as he hath before written, your promise made should surely be broken, by the persuasion of the clergy, which would affirm that promises made with heretics ought not to be kept.’ Tyndale then seemed ‘somewhat fearful’ at being with the king’s agent in an isolated and darkening field. Evening was coming and Tyndale scurried down a road leading away from Antwerp. Vaughan presumed that Tyndale had doubled back to Antwerp as soon as he was safely out of sight.

‘Hasty to pursue him I was not, because I had some likelihood to speak shortly again with him,’ Vaughan explained to the king. ‘To explain to your majesty what, in my poor judgement, I think of the man, I ascertain your grace, I have not communed with a man—’ At this point, the copy of Vaughan’s letter is torn off. Henry himself may have ripped it across. The letter certainly angered him. Cromwell’s notion of having Tyndale return to England was acceptable only if he came as a penitent, to whom the king could graciously extend his mercy and protection. Yet, far from being humble and contrite, the fellow complained that the king was ‘unkind’ to God and ungrateful for the support given to him in

Prelates

. Moral lectures were not the way to Henry’s heart, but to the scaffold; that this did not occur to Tyndale shows once more his innocence, or blindness, to human frailties and vanity. He was more astute in matters of safety. He was right to fear that a safe conduct might be broken for a heretic. This was, as we shall see, More’s exact opinion.

Vaughan met Tyndale twice more. He informed the king on 20 May that he had again urged Tyndale to return to England. He had shown the exile an extract from a letter he had received from Cromwell. In it, the royal secretary said that he hoped that Tyndale might be converted from ‘the train and affection which he now is in’, and disavow the ‘opinions and fantasies sorely rooted in him’. If this happened, Cromwell continued, ‘I doubt not but that the king’s highness would be much joyous’, so much so that the king would be inclined ‘to mercy, pity and compassion’. Vaughan said that these words were of such sweetness and virtue ‘as were able to pierce the hardest heart of the world’. When Tyndale read them, he said, he became ‘exceedingly altered’, tears stood in his eye, and he murmured: ‘What gracious words are these!’

Tyndale proposed a deal, but it did not compromise his demand for the English Bible one jot. ‘If it would stand with the king’s most gracious pleasure to grant only a bare text of the scripture to be put forth among his people,’ Vaughan reported him saying, ‘like as is put forth among the subjects of the emperor in these parts, and of other Christian princes, be it of the translation of what person soever shall please his majesty, I shall immediately make faithful promise never to write more, nor abide two days in these parts after the same: but immediately to repair unto his realm, and there most humbly submit myself at the feet of his royal majesty, offering my body to suffer what pain or torture, yea, what death his grace will, so this be obtained. And till that time, I will abide the asperity of all chances, whatsoever shall come, and endure my life in as many pains as it is able to bear and suffer.’