Read Dancing in the Darkness Online

Authors: Frankie Poullain

Dancing in the Darkness (6 page)

‘M

aking it’ is a lot like an endurance event: it’s a triathlon of vocation, desperation and balls. If I was being cheesy, I’d say Dan had the vocation (talented and doing it for the right reasons), I had the desperation (getting on a bit and with a point to prove to my dad) and Justin had the balls (space-hoppers). As for Ed Graham, a hard-drinking but loveable school friend of theirs chosen to be the Darkness drummer, he was just desperate for the

vacation

, and maybe some cheese balls into the bargain.

If you are driven by only one of these factors, then you are doomed to fail. You may as well enjoy that endless vacation and a family-size box of cheese balls. And maybe that’s not such a bad thing: at the end of the day, we are all bitches to the record industry. And the record-company bosses

are pimps who believe that the most important thing is to put on a proud face when sucking the collective cock of the masses.

London’s full of bed-sit geniuses going nowhere. And the other type – stubbornly determined ‘Johnny no talents’ ploughing a fruitless furrow. The former have vocation and the latter have desperation in spades. Of course, for desperation you can just as easily read ‘determination’, but the fact remains that there’s nothing sadder than unfulfilled dreams and, when it comes to fulfilling your dreams, chemistry is everything.

To some, our uncanny chemistry was a happy accident, but there was nothing accidental about Dan answering his vocation to be the guitarist. It takes talent to be the guitarist in a rock band, after all. Then there was Justin, with his balls, and only too delighted to put them on the line. Lastly there was myself as a bass player. If you’re so bloody minded that you can’t see you’re unsuited to performing in a glam-metal outfit, you’ll do anything, even play bass guitar, just to prove a point. As this book progresses, we’ll try to discover what that point was.

I

was no great shakes as a bassist. That was obvious. At least it was to me, Justin, Dan and Ed, who’d be the first to admit he wasn’t exactly a virtuoso himself. And it wasn’t just that no one else seemed to notice. Strangely, though, everyone insisted we were all great musicians. ‘You guys can really play!’ wasn’t just the consensus, it carried a similar approval rating to the Nazis in late-1930s Germany. Not that myself and Ed coerced impressionable music fans into that way of thinking, you understand.

As I mentioned earlier, Justin and Dan were technically very gifted musicians. From an early age they were immersed in classic rock, playing and listening to Queen, AC/DC, Led Zeppelin and Foreigner (irreverent Justin loved eighties metal while reverential Dan was the seventies man

*

). On the surface, then, it was inappropriate of them to join forces with myself and Ed, who had more idiosyncratic musical tastes – as well as an inability to play in time with each other.

But ‘inappropriate’ is what makes a band special and unique: the Manics’ Nicky Wire and Mötley Crüe’s Nikki Sixx were, how shall we say, sometimes somewhat inept. You can’t plan chemistry – and don’t let the scientists tell you it’s possible, they’re only protecting their livelihoods. Besides, our music was the antithesis of science in every way. (Once, I overheard a sound engineer talking about photosynthesis backstage. I assumed he wanted a snap of Justin’s synthesizer and told him to go right ahead.) What made it interesting was that we all approached our instruments differently. And in mine and Ed’s case, that invariably meant hammering away, like a monkey at a typewriter.

*

Eighties hair metal was sillier and more fun than the more authentic seventies hard rock, but the fact remains that no one could make up their mind if we were an eighties or a seventies throwback – only that we were a throwback. This ongoing ‘Quiche or Fondue’ inquisition grated after a while.

I

n early 2003, we were a buzz band on the independent label Must Destroy, looking to break through and achieve commercial success. Justin started working out after being branded ‘a porky Austin Powers lookalike’ and I took to cultivating a pirate headband and scowling onstage demeanour. Late one night at a music-industry party in a Portuguese café near Westbourne Park, I found something to

really

scowl about, after crossing swords with seven gacked-up gatecrashers – an incident I’ll refer to as ‘Snow White And The Seven Chavs’.

I have a quick temper when people pick on me because, quite frankly, I don’t think it’s fair. That’s my French sense of injustice for you. I pick on myself enough without any help from anyone else. But this went way beyond a ‘pick on’ – I found myself being

dragged out to a car park and savagely assaulted by the Seven Chavs high on Snow White, one of whom was probably called Sniffy and presumably there must have been a Snorty in there as well.

It was a bit like the jungle bee attack, but with bottles, glasses and brutal kicks instead of stings. Again, it took me a while to figure out what was happening. What had I done wrong? At least the bees had a proper excuse – in destroying their nest, I had ended their civilisation. It’s not as if I’d ended these guys’ civilisation.

But, mercifully, there was help at hand. A saint was watching over me, and not just any old saint, but a

leader

of saints: Steve Finan, the manager of girl group All Saints. Steve only got involved because we’d been introduced earlier in the evening, and I’m glad he did, because he happened to be a first dan black belt in Taekwondo.

According to onlookers, what happened next was ‘like something out of a Jackie Chan flick’, as he laid waste to their Burberry asses one by one. In the midst of all this, I’d been dragged into a taxi, bloodied and battered, and was speeding down the Westway with hulking sound engineer Pedro, who’d also battered one of them before carting me away. I felt accountable and wanted to go back but

was assured that Steve Finan was OK (though he had, in fact, slipped and gashed his head on the gravel) and, it seemed, the Seven Chavs had disappeared into the night with their Snow White. I’d lost my lucky Scottish thistle pendant, an engraved hip flask (a gift from our then independent record company Must Destroy) and a favourite pin-stripe jacket. Several shades of shit had been knocked out of me, but there was still life to cherish, thanks to this Finan phenomenon.

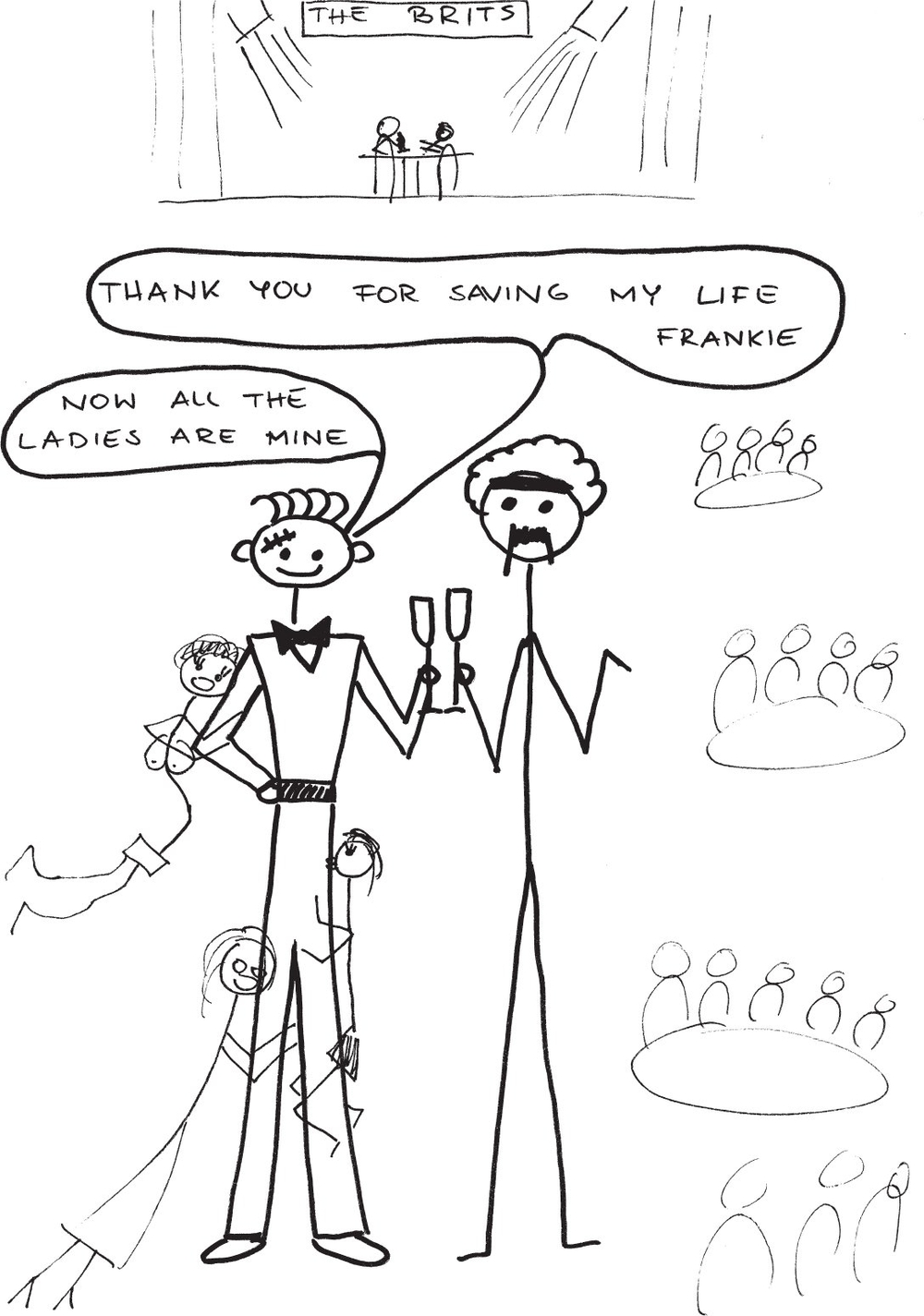

The next day, I called him and stammered out my thanks. He’d had 22 stitches on the gash above his eye, leaving an unmistakable scar. The guilt burned deep within me. Would he at least allow me to pay for cosmetic surgery? Steve simply laughed and mumbled something about insurance. I had an innate desire to buy this saviour of mine a drink, yet, perversely, whenever we bumped into each other after that it was always an awards bash of some kind where the booze was free. Terrific news for my accountant, but not so good for the old conscience. The Kerrang! Awards, the Mercury Music Prize, the Brits and the Ivor Novellos – we were up for the lot and at each the customary Steve Finan greeting, Action Man scar above his eye, and apologies swatted away like so many bothersome chavs.

Three years later, I was in my chateau (more of which anon) when friends arrived from the UK with a copy of the

Sunday Mirror

. It was a sweltering summer evening as we sat in the cool stone kitchen drinking Kronenbourg 1664 and listening to Serge Gainsbourg on the radio. Beneath the headline ‘Denise Lewis’s Secret Lover Revealed’, I caught a familiar printed name in the subheading, then immediately recognised the face in the picture. It was Steve Finan again. I’ve heard that they’re an item now, the heroine of British athletics and the hero of this book’s author, and I’m convinced it’s all down to that lucky scar.

Now I know it’s not the end of the world to get into a fight – not if it provides a valuable moral lesson and source of future inspiration. Maybe that’s why people go to war? By doing something stupid – getting the shit kicked out of me – I had unsuspectingly created a platform for the world’s first music-business superhero.

Holy sunburst of a new religion:You can only save your own life by first saving the life of someone else.

G

od doesn’t exist; you only get what you give. Then again, if you only get what you give, maybe he does exist? (That’s a logical fallacy – Ed

*

.) We were just working hard trying to fulfil our destiny. The gigs were going well but we still didn’t possess a hit, a song that summed us up. Every band needs a signature tune to connect to an audience, a musical placard that proudly states, ‘THIS IS US’, in big bold letters.

Take ‘Creep’ by Radiohead, for example. That song distils the very essence of Thom Yorke and speaks to the millions out there who feel the same. I was living in a bed-sit and it was cold; I suppose I knew how poor Thom felt. Granted, it was in Primrose Hill, but I was spending my dole cheque on rehearsals and surviving on cheese-and-pickle toasties. I wished

I

was special, but until we proved we could pen a modern classic and connect to our audience, I was destined to remain very un-special. In fact, we all were.

We’d write songs sitting around what we called ‘the table of truth’ in my pokey bed-sit, puffing on joints and absorbing those toasties – if cheese made you dream, surely it could inspire you creatively too? The Branston pickle at least encouraged the odd burp, which might accidentally unearth novel rhythmical ideas.

During one such session, and interrupting a crucial Manchester United Champions League match, Justin strummed an odd back-to-front riff through one of those toy matchbox-sized mini Marshall amps. It sounded upbeat and rhythmical, with just a hint of The J Geils Band’s ‘Centerfold’.

Then the chorus chords kicked in and words seemed to trip over themselves like blind chipmunks. ‘There’s a chance we can make it now’ just had to be in there. And, in a brazen attempt to make it more eighties than chunky cream leg warmers, ‘Just listen to the rhythm of my heart’ and ‘We’ll be rockin’ till the sun goes down’ lined up

alongside. The song’s long bridge notes and chorus crescendo really couldn’t have been a better showcase for Justin’s soaring falsetto – and, it has to be said, it was he who composed the lion’s share of this metal classic.

Two long years and one major recording contract later, the song ‘I Believe In A Thing Called Love’ became an international smash that made our short but lucrative careers. It’s living, breathing testament that you can squeeze plenty of sunshine out of a cold, damp bed-sit, because without that song we’d have achieved nothing internationally and probably sold a fraction of the 3.5 million albums we shifted worldwide.

Songwriting is a bit like gold mining: you’ve got to stick at it, put the hours in, and occasionally rip someone off before they rip you off. Otherwise, you’ll end up with chicken nuggets instead of golden ones.

*

Don’t worry I haven’t hired former Darkness drummer Ed Graham as a proof-reader – the ‘Ed’ in question is, in fact, the book’s editor.