Read Death at the President's Lodging Online

Authors: Michael Innes

Tags: #Classic British detective mystery, #Mystery & Detective

Death at the President's Lodging (6 page)

“The

Deipnosophists

,” Appleby was murmuring; “Schweighäuser’s edition…takes up a lot of room…Dindorf’s compacter – and there he is.” He pointed to the corner of the lower shelf where the same enormous miscellany stood compressed into the three compact volumes of the Leipsic edition. Dodd, somewhat nonplussed before this classical abracadabra, growled suspiciously: “These last three are upside down – is that what you mean?”

“Well, that’s a point. How many books do you reckon in this room – eight or nine thousand, perhaps? Just see if you can spot any others upside down. It’s not a way scholars often put away their books.”

Dodd declined the invitation. “I thought you said something about candles. Is it all a little classical joke?”

Appleby straightened himself from examining the lower shelf and pointed gently to the polished surface, breast high, of the top of the bookcase they were examining. A few inches from the edge farthest into the bay was a small spot, about half an inch in diameter, of what appeared to be candle-grease.

“Some cleaning stuff,” said Dodd. “Beeswax preparation, perhaps. Careless servant.”

“A burglar – an amateur burglar with a candle?” Appleby suggested.

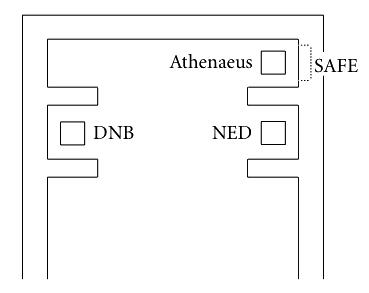

Dodd’s response was immediate: he vanished from the room. When he returned, Appleby was on his knees beside the body. “You were right, Appleby,” he announced eagerly. “Only some sort of furniture cream is ever used on these bookcases. And they were done yesterday morning. The housemaid swears there wasn’t a speck on them then – and she’s a most respectable old person.” He paused, and seeing that Appleby’s inspection of the body seemed over, added: “I’ve something of my own to show you in that alcove. It made me jump to your suggestion of a burglar at once. We didn’t ignore the nine thousand books altogether, you know.” He led the way back to the bay and paused, this time not before the revolving bookcase but before the solid shelves of closely packed books behind it. Putting his hand behind what appeared to be a normal row he gave a sharp pull – and the whole swung easily out upon a hinge. “Dodge they sometimes decorate library doors with – isn’t it? And look what’s behind the dummies.” What was behind, sunk in the wall of the room, was a somewhat unusual, drawer-shaped steel safe.

“The sort of burglar who potters about with a candle,” remarked Appleby, “wouldn’t have much of a chance with that. Difficult to find too, unless he knew about it. Not that I expect you knew about it?”

Dodd had not known. He had found the safe in the course of a thorough search. The thousands of books had not been moved from their shelves, but every one had been pressed back as far as it would go to ensure that no discarded weapon lay anywhere concealed on the shelving between books and wall. He was positive, however, that the searchers were not responsible for turning the smaller Athenaeus. He had examined its particular revolving bookcase himself – missing, he admitted, the candle-grease – and had found it unnecessary to take any of the books out. He had also himself inspected the whole bay and had come upon the concealed safe in the process.

Appleby’s eye travelled once more along the endless rows of books, rapidly noting the character of the dead man’s library. But it was the physical appearance of hundreds of heavy folios on the lower shelves which prompted his next remark. “Lucky he was shot through the head, Dodd. Do you see what a job that has saved us?” And seeing his colleague’s puzzled look he went on: “Fancy it this way. Umpleby wants to commit suicide. For this reason or that – just out of devilment, perhaps – he decides to conceal the fact. Well, he takes any one of these books, probably a big one, perhaps quite a small one” – here Appleby tapped a stoutish crown octavo – “and he hollows out a little nest in it – large enough to hold an automatic. He holds it open with his left hand, close by its place on the shelf. Then he places the pistol just where a careful study of anatomy tells him, fires, slips the pistol in the book and the book in its place, staggers across the room and falls – just where you see him!”

Following Appleby’s pointing finger, Dodd strode across the room to where the body lay. The small round hole, central in the forehead of the dead man, reassured him – but he glanced with new curiosity nevertheless at the vellum and buckram and morocco rows, gleaming, gilt-tooled, dull, polished, stained – the representative backs of perhaps four centuries of bookbinding. But Appleby, with a gesture as if he had been wasting time, had turned back to consider the concealed safe. “Fingerprints?” he asked.

Dodd shook his head.

“None at all?” pursued Appleby, interested.

But this time Dodd nodded. “Yes,” he said, “I’m afraid so. Umpleby’s own. No one has been feeling the need of polishing up after himself. It looks as if the safe has been undisturbed. One thing’s queer about it all the same – and it’s this. Not a soul seems to know anything about it. I asked fishing questions of everyone the least likely – ‘Do you happen to know where the President kept his valuables?’ and that sort of thing. And then I asked outright. Slotwiner, the other servants, the Dean and the rest of the dons – none of them admitted to knowing of its existence. And there’s no key. It’s a combination lock and a combination lock only – not the kind where the combination opens to show a keyhole. Further than that I haven’t had time to follow the thing up.”

At the mention of time, Appleby looked at his watch. “I’m due for the Dean,” he said, “and you for your supper and a rest. They’ll want to take the body now, I expect.”

Dodd nodded. “The body goes out to the mortuary,” he agreed; “the room’s locked up and sealed and you take the key. And it’s for you to say when we bring a sack for these blasted bones.”

Appleby chuckled. “I see it’s the ossuary that really disturbs you. I think it may help a lot.” He picked up a fibula as he spoke and wagged it with professionally excusable callousness at Dodd. And with an association of thought which would have been clear to that efficient officer only if he had been a reader of Sir Thomas Browne he murmured: “What song the Sirens sang, or what name Achilles assumed when he hid himself among women…”

The fibula dropped with a little dry rattle on its pile as Appleby broke off to add: “Nor is the other question, I hope, unanswerable.”

“

Other

question?”

Appleby had turned to the door. “Who, my dear Dodd, were the proprietaries of these bones? We must consult the Provincial Guardians.”

The Reverend the Honourable Tracy Deighton-Clerk, Dean of St Anthony’s, contrived, though still in middle age, to suggest the great Victorians. His features were at once wholly strong and wholly benevolent, evoking, even to a hint of side-whisker, the formidable canvases of G F Watts. His manner was a degree on the heavy side of courtesy and not at times without that temerarious combination of aloofness and charm which used to be attempted, some two generations ago, by those who had once glimpsed Matthew Arnold. He had a fancy for himself in the role of

ultimus Romanorum

; the last representative of a clerical and leisured university, of an academic society that was not cultured merely but also Polite.

The psychologically-minded Slotwiner (who was said to model himself not a little on Mr Deighton-Clerk’s manner) might have remarked that in the Dean’s

persona

the episcopal idea had of late been rapidly developing. Indeed, the episcopal idea was hovering round him now, a comforting penumbra to the disturbing situation which confronted him as he stood, in elegant clerical evening dress, before the fireplace of his study.

It was a room in marked contrast with the sombre and somewhat oppressive solidity of the dead President’s apartment. Round a delicate Aubusson carpet, on which undergraduates instinctively trod as diffidently as if they had been schoolboys still, low white book-shelves enclosed the creamy vellum of the Schoolmen and the Fathers. The panelling was cream, its delicate Caroline carving touched with gold. The ceiling was cross-raftered in oak and from the interstices there gleamed, oddly but harmoniously in blue and silver, the twelve signs of the zodiac. Over the fireplace brooded in austere beauty one of Piero della Francesca’s mathematically-minded madonnas, the blue of her gown the same as that amid the rafters above. The whole made a pleasant frame – and the rest of the furnishing was ingeniously unnoticeable. Mr Deighton-Clerk and the Virgin between them dominated the room.

But at the moment the Dean was feeling in a scarcely dominant mood. He was doubting his own wisdom – a process he disliked and avoided. But he could not but doubt the wisdom of the action he had taken that morning. To insist on bringing down a detective-officer – no doubt a notorious detective-officer – from Scotland Yard because of this appalling affair! This was surely to court the widest publicity – to say the least?

Mr Deighton-Clerk’s gaze went slowly up to the ceiling, as if seeking comfort in his own private astrological heaven. Comfort came to him in some measure as his eye moved from

Cancer

to the taut form of

Sagittarius

. He had taken energetic action. And was it not (but here the thought floated only in the remoter regions of the Dean’s brain) – was it not the capacity for energetic action that was called in question when the possible preferment of a mere scholar was canvassed? At this moment the Dean’s eye, voyaging still among his rafters, rested on

Aquarius

, “the man who bears the watering-pot,” as the rhyme has it. And by processes connected perhaps with the association

cold

-

douche

, the full mischief of the business was brought home to him more vividly than it had been yet. To be mixed up in a scandal under these outrageous circumstances of modern nationwide publicity! Hardly helpful, he thought grimly; hardly helpful whatever solution of the business the police achieved. That there would be no sensational domestic revelation – it was for that that he must hope and pray. And it was of that that he had, in the course of the day, almost succeeded in convincing himself. (

Pisces

, as if they had ventured some contradiction, came in for a stern glance here.) In the long run it would not be left in any doubt that the crime (crime in St Anthony’s!) was an outside affair – the purposeless stroke, perhaps, of a madman.

But here

Libra

, the scales, asserted themselves. There was matter to be balanced against that hope. Let this detective be anything but a model of discretion, let him have a taste for amusing the public, and there might be an uncomfortable enough period of startling, if improbable and unprovable, theories blowing about. The unlucky topographical circumstances of the deed, the Dean had realized from the first, set suspicion flowing where it should be fantastic that suspicion should flow… He frowned as he thought of his colleagues under suspicion of murder. How would they stand badgering by policemen, coroners, lawyers? How, for that matter, would he stand it himself? Praise Providence, he and his colleagues were all demonstrably sane.

Those bones! They were mad. Last night, when he had viewed them, he had been annoyed by them. He had at first been more annoyed by the bones (he recollected with some discomfort) than distressed about the tragedy. He had been annoyed because he had been bewildered (Mr Deighton-Clerk disliked being bewildered – or even slightly puzzled). But later he had felt – somewhat incoherently – a possible blessedness in them: their very irrationality removed the crime somehow from the sinister and calculated to the fantastic. They were a sort of bulwark between the life of the college, in all its measure and reason, and the whole horrid business.

And then – and it was as if

Leo, Taurus

and

Aries

had roared, bellowed, butted all in a moment – Mr Deighton-Clerk realized what a feeble piece of thinking this was. The first thing that this detective would suspect about the bones was that they were some sort of blind or bluff. How obvious; how very, very obvious! Indeed, were the man literate, his mind might run to some notion of the touch of fantasy, the vivid dash of irrationality, that it might please an intellectual and cultivated mind to mingle with a laboriously calculated crime… A mixture, thought Mr Deighton-Clerk, somewhat in the manner of Poe.

Decidedly, he did not like the bones after all. And suddenly he realized that, subconsciously, they had profoundly disturbed him from the first. Sinister, grisly objects – surely they were striving to connect themselves with…something forgotten, suppressed, unconsidered on the borders of his consciousness…? He was nervous. The dock (he heard his own inner voice absurdly exclaim) is yawning open for us all…