Read Evolution's Captain Online

Authors: Peter Nichols

Evolution's Captain (9 page)

Other hosts would have been FitzRoy's acquaintances in the scientific and professional world, such as Roderick Murchison, a foremost geologist who later became president of the Royal Geographic Society and remained keenly interested in the Fuegians' welfare for years after meeting them; Cambridge professor-geologist Adam Sedgwick, one of the most influential educators of his day; probably Charles Lyell, the young barrister-turned-geologist, whose book

Principles of Geology

enormously influenced FitzRoy's (and everyone else's) thinking about the age of the world and its natural history; and his navy friends: Francis Beaufort, the hydrographer of the British Navy who later developed the Beaufort wind scale; Sir John Richardson, the retired naval expert on the natural history of the Arctic; and many others who wished to see these examples of “brute Creation” whom FitzRoy had plucked from the wild and given a swift makeover as English gentlefolk.

On these occasions, FitzRoy's specimens would be encased in their stiff, Sunday-best clothes, rather than their schoolday garb,

and would arrive at their hosts' homes with him in his carriage, drilled in the basic graces and polite exchanges. They were questioned about their native land and about their present circumstances; they were served refreshments and full meals. They were given presents. Their answers, in broken English, and their developing table manners, invariably charmed and fascinated their hosts.

The culminating pinnacle of the Fuegians' social forays was an audience with the new king, William IV, and his wife, Queen Adelaide. A quiet man and lackluster monarch with a disdain for pomp and ceremony, William had been welcomed by the British public and its government on succeeding his brother, George IV, whose tabloid escapades had been an embarrassment to the country. Never expecting to become king, William had lived quietly with his mistress, Mrs. Dorothea Jordan, for twenty years and fathered ten illegitimate children by her. None of these was a possible heir, so on accession to the throne in 1830 he married Adelaide of Saxe-Coburg and Meinengein, who bore him two daughters, both of whom died in early childhood.

*

William had joined the Royal Navy at the age of thirteen, traveled widely, and was known as the Sailor King; he hungered for associations beyond the court, for his earlier connection with the exciting world of travel. As king, he often invited explorers and adventurers to meet with him and questioned them about their exploits. With his naval connections and interest, he clearly knew about Captain FitzRoy.

The only record of the visit is FitzRoy's.

During the summer of 1831, His late Majesty expressed a wish to see the Fuegians, and they were taken to St James's. His Majesty asked a great deal about their country, as well as themselves; and I hope I may be permitted to remark that, during an equal space of time, no person ever asked me so many sensible

and thoroughly pertinent questions respecting the Fuegians and their country also relating to the survey in which I had myself been engaged, as did His Majesty. Her Majesty Queen Adelaide also honoured the Fuegians by her presence, and by acts of genuine kindness which they could appreciate, and never forgot.

It is Fuegia Basket who is singled out for mention in FitzRoy's account of the meeting. The sweet natural empathy that had prevented him from giving her up in Tierra del Fuego drew Adelaide's greatest attention. The childless queen was captivated by the gamine native girl in her Christian frock.

She left the room, in which they were, for a minute, and returned with one of her own bonnets, which she put upon the girl's head. Her Majesty then put one of her rings upon the girl's finger, and gave her a sum of money to buy an outfit of clothes when she should leave England to return to her own country.

As an accomplished amateur scientist and already a renowned explorer, FitzRoy was exhibiting “his” Fuegians as performing curiosities, just as Professor Challenger would unveil his leathery pterodactyl to the members of the Zoological Institute at the conclusion of Arthur Conan Doyle's

The Lost World

. They were the fruit of the obsession he had picked up, like sea fever, in Tierra del Fuego, though his interest in them for their own sakes, and for their welfare, was altruistic and sincere. But he felt more than a professional glow of pride at their accomplishments. The space he gave to them in the

Narrative

, and the language of concern for their well-being and happiness, indicate a strong emotional involvement. FitzRoy was still a young man, only twenty-five in that winter of 1830â1831 when he stepped out in English society with his charges, unmarried and living alone, except for his servants. He almost certainly felt for the two younger Fuegians, children in his care, a fatherly emotion. Perhaps even love.

Â

When not squiring his Fuegians about on their social engagements

, FitzRoy spent the winter and first three months of 1831 in the Hydrographic Office of the Admiralty supervising the drawing of charts based on his surveys of Tierra del Fuego, and writing the sailing directions to accompany them. The vast labyrinth of southern South America still remained largely unexplored, yet FitzRoy, Captain Phillip Parker King, and the late Captain Stokes and his more functioning officer Lieutenant Skyring had achieved a great deal for vessels navigating between the Atlantic and the Pacific.

Two escape routes from the southern part of the Magellan Strait direct to the Pacific Ocean had been charted, enabling westbound vessels encountering northwest winds to make their way more quickly to the open sea; an inshore route had been found on the west coast from the Gulf of Peñas direct to the Magellan Strait for small vessels using the prevailing northwest winds; the rugged coasts around Cape Horn had been charted, as had the Strait of Lemaire; and the remote and dangerous Diego Ramirez Islands had been fixed where they lay, far out to the southwest of Cape Horn. (

The Admiralty Chart

, Rear Admiral G. S. Ritchie)

British Admiralty charts had been made available for sale to the merchant fleets of the world since 1821, and the new charts and sailing directions that were the fruit of the

Beagle

's and the

Adventure

's commission would have been of invaluable assistance to mariners and navigators for the cost of a few shillings.

Four draughtsmen worked in the Hydrographic Office. These men drew the charts from FitzRoy's and King's drawings, under their supervision. When the drawings were completed they were taken to Messrs Walker of Castle Street, Holborn, for engraving onto copper plates. The plates were delivered back to the Admi

ralty, where they were used on the navy's copper press, by its own copper printer and assistant, whenever a run of charts was required.

FitzRoy was doing this work at a time of signal change in the Hydrographic Office, under the direction of a figure whose name is known to seamen the world over today. Two years earlier, Captain Francis Beaufort had been appointed Hydrographer of the Navy (the choice had been between Beaufort and Captain Peter Heywood, the last survivor from the

Bounty

mutiny). When Beaufort took over the chair in May 1829, the Napoleonic wars had been over for fourteen years, and Britain's navy was in the early days of a century of peace in Europe that would last (apart from the interruption of the Crimean War) until the outbreak of World War I. The navy's interest had shifted from defense to the guardianship of its empire, and facilitating the expansion of trade and exploration. Beaufort intensified surveying efforts across the globe, and within a few years of his appointment sent ships and surveyors back to South America; to Africa, Australia, New Zealand and New Guinea, the South China Sea, the Caribbean, Canada, the Mediterranean; and to the home waters around the British Isles. A number of these surveyor-captains who became famous for their workâSkyring, Lort Stokes, and Sulivanâgot their training with FitzRoy aboard the

Beagle

.

Beaufort was fifty-five when he became hydrographer. His interest in charting came from his father, the Rector of Navan, County Meath, Ireland, an amateur cartographer who had made an excellent map of Ireland. Beaufort joined the navy at thirteen and served under several surveying commanders, including Alexander Dalrymple, who had prepared a chart of descriptions of wind strengths, numbered 0 (“flat calm”) to 12 (“a hurricane such that no canvas could withstand”). Beaufort refined Dalrymple's scale to give wind speeds in nautical miles per hour and accompanying descriptions of sea states for each “force” on the scale (for example, “Force 8; 34â40 n.m.p.h; Near Gale; Height of Sea in ft: 18; Deep sea criteria: High waves of increasing

length, crests form spindrift”). He persuaded the navy's captains and navigators to employ it in descriptions of sea conditions in their logs and official reports, and today the Beaufort Scale is used and understood by sailors the world over.

Like FitzRoy, Beaufort had scientific interests that took him far beyond the navy and made him useful friendships. He was a Fellow of the Geological Society, the Royal Society, the Astronomical Society, and a leading figure in the founding of the Royal Geographical Society in 1830, just as FitzRoy was returning from Tierra del Fuego. The rapid efflorescence of science in the early nineteenth century led the Admiralty, with Beaufort's urging, to form its own scientific branch in 1831, to contain the Hydrographic Office, the Royal Observatories at Greenwich and Cape Town, the Nautical Almanac and Chronometer Offices, and later the Compass Office. Beaufort was the ideal link between the musty, wooden world of the Georgian navy and the progressive, expanding, enlightened Victorian era that was about to take over.

A sudden and important presence in the Hydrographic Office over the winter and early spring of 1830â1831, FitzRoy met with his superior regularly. Half Beaufort's age and always fully conversant with the latest scientific developments, FitzRoy not surprisingly became one of the hydrographer's favorites.

Lucky for him. He was soon to have urgent need of Beaufort's help.

Â

As the two Fuegian children continued to thrive at Walthamstow

, their adult compatriot sank deeper into isolation. Cut off from any meaningful contact with the world, he was also cut off as a man. FitzRoy estimated York Minster's age as twenty-six in 1830. He was in the physical prime of his life. At home, among his own people, he might have had (possibly he did have) a wife. Certainly he would have been having sex. The straitlaced confines of the church-run Infant School, the constant supervision of Schoolmaster Jenkins, his wife, the Reverend Wilson, and

Coxswain Bennett, whom FitzRoy had installed in Walthamstow to keep him posted on the Fuegians, and the unceasing importuning to strict Christian behavior must have been a living hell to a healthy, primitive man. The flourishing prostitution industry in London was far beyond his reach, geographically and socially.

There is no record of any associations that might possibly have occurred between York Minster and the maidservants and women he would certainly have come into contact with at Walthamstow. There is only the known fact that at some point during their stay there, he fastened his sexual attentions on the ten-year-old Fuegia Basket.

I

t was FitzRoy's man on the scene, Coxswain Bennett, installed

in rooms nearby, whose worldly experience beyond straitlaced Walthamstow made him the best and earliest witness to what was afoot.

And so it went until late one afternoon when Coxswain Bennett happened down the hedge by the Infants School. Fortunately he had left his sharp cutlass at the inn. But, shifting his quid, spitting to windward, and with a look of determination on his mahogany face, he grabbed Fuegia, as York disappeared through the hedge and, turning her over his honest knee, spanked her soundly.

“It no me, no me!

York, he York, only York,

” she pleaded.

“And so, sir,” reported the coxswain, “I quits aspankin' of her fat little bare bottom, sir, and sets her downâ¦but the way that York's been aglarin' at me since has me awearin' of my cutlass, an' I sleeps with it, sir, when I does sleep.”

“Bennett, this is the most terrible thing that yet has happened. I'd ratherâI'd rather see her in a Christian grave, like poor Boat.” Captain FitzRoy, in the snug at the inn, to which he had hastened by private appointment, broke a life's rule. He ordered port, and he and his coxswain fortified themselves in private.

“Them heathen women ripens rapid, sir. I mind me, in Calicut.”

“Yes, Bennettâyes, I know. But what

is

to be done?”

“Sail, sir, sez I. Slip the cable, Captain, an' I'm with you, sir.”

This account comes from

Cape Horn

, by Felix Reisenberg, a generally splendid, thoroughly researched history of Cape Horn and the mariners and natives who have made the place famous. Reisenberg, a seaman of wide experience, a Columbia graduate, engineer, maritime historian and writer, had a novelist's feel for situation and character and relates history with gusto. But he was writing a book for the popular market and had no qualms about taking some liberties. This episode, suggesting that Coxswain Bennett caught York Minster and Fuegia Basket

in flagrante delicto

down by the hedge at the Infants School, is clearly one of them. Fanciful, unsupported, and written as if Reisenberg had stayed up too late reading

Treasure Island

, it's the suggestive missing link in the story of FitzRoy's Fuegians. It is what can be inferred from what was known and subsequently happened, but is nowhere reliably recorded.

Most discordant is Reisenberg's FitzRoy. The captain wringing his hands and asking his coxswain “What

is

to be done?” sounds wholly out of character for the imperious young FitzRoy. Maddeningly, tantalizingly, Reisenberg frequently “quotes” the garrulous coxswain, making of him a salty and salacious commentator on great doings that have been handed down and sealed in the often dull and cloudy aspic of nineteenth-century prose.

But during the spring of 1831,

something

happened between the Fuegians at Walthamstow to make FitzRoy suddenly and drastically curtail his original plans to educate them “and, after two or three yearsâ¦take them back to their country.” Because by June, after the Fuegians had been in Walthamstow only seven months, FitzRoy was going to extraordinary lengths, and digging deep into his own pockets, to get them out of England and back to Tierra del Fuego as soon as possible.

His official work supervising the production of charts from his surveys was finished in March. “From the various conversations which I had with Captain Kingâ¦I had been led to suppose that the survey of the southern coasts of South America would be continued; and to some ship, ordered upon such a service, I had looked for an opportunity of restoring the Fuegians to their native land.” But there was no immediate prospect for a further South American commission. Despite Beaufort's personal desire that the survey of South American waters be continued, and FitzRoy's accomplishments there, the Admiralty considered an early return to Tierra del Fuego unnecessary in the spring of 1831. Yet, certainly within the two- to three-year time frame of FitzRoy's original plan for the Fuegians, he would have found a ship bound around Cape Horn that could have taken his passengers. But now he “became anxious about the Fuegians.” And, after so closely detailing his hopes for them, that is all he writes about the sudden turnaround of his scheme.

So anxious that he arranged to charter a small merchant vessel, the

John of London

, to carry him, Coxswain Bennett, the three Fuegians, and the supplies amassed and donated to them back to Tierra del Fuego, and eventually land him and Bennett in Valparaiso, where they could find a ship returning to England. No little jaunt this, the cost of chartering the

John

was £1,000âthe equivalent of the price of a London townhouseâto which FitzRoy would have added food and supplies for himself and his retinue for at least six months, plus salary for Bennett.

York Minster's attentions to Fuegia Basket were almost certainly responsible for such an extreme departure from his initial design. FitzRoy later admitted as much.

He had long shown himself attached to her, and had gradually become excessively jealous of her goodwill. If anyone spoke to her, he watched every word; if he was not sitting by her side, he grumbled sulkilyâ¦if he wasâ¦separatedâ¦his behaviour became sullen and morose.

An episode like the one imagined by Felix Reisenberg, or the slightest suggestion of it, would have been disastrous for FitzRoy. The unseemly possibility that Fuegia Basket might become pregnant was the least of it. This indication of ineradicable savagery breaking through the civilizing glaze on his charges threatened to destroy all the goodwill that had been showered on the Fuegians and FitzRoy himself by the royal family, the court, the Admiralty, FitzRoy's friends, the public at large, Reverend Wilson, and the kind people at Walthamstow. All had embraced the Fuegians and taken deeply to heart FitzRoy's own pious sentiment that they offered a rare and quite clearly divinely engineered opportunity not only to deliver three heathen souls from the perils of savagery but to return them home to plant a holy seed that might grow and spread across a Godless continent. Reaction to news that the sweet child adored by so many was having sex with a hulking, unreformable savage at the Walthamstow Infants School would be catastrophic. It could mean disgrace for FitzRoy and the end of his naval career.

On a more personal level, this development deeply shook FitzRoy's faith in his grand scheme. He was so certain of the benefits of exposure to the Anglo-Christian civilization that he saw physiological proof of it: he believed the Fuegians' physical features were altered and improved by their stay in England.

The nose is always narrow between the eyes, and, except in a few curious instances, is hollow, in profile outline, or almost flat. The mouth is coarsely formed (I speak of them in their savage state, and not of those who were in England, whose features were much improved by altered habits, and by education).

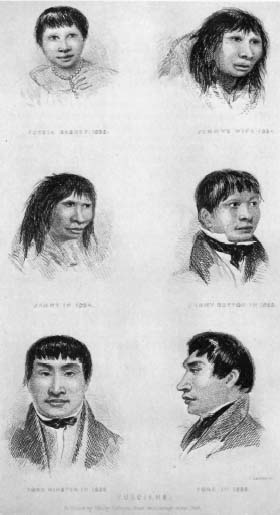

FitzRoy's own ink portraits of Jemmy Button reflect this clearly. A comparison between Jemmy in his “savage” state, and the “English” Jemmy, wearing a high collar, cravat, and frock coat, shows features altered as if by cosmetic surgery: Anglo Jemmy's nose and mouth are finer, flared and expressive, the

eyes bright with acuity as if he were attending a lecture on paleontology, his posture upright and proud. Savage Jemmy looks a million years older, a Neanderthal version with an entirely different cranium shape, crouched and hulking, thicker-featured, with dull-witted eyes sunk beneath a heavier brow.

FitzRoy's Fuegians, from his own drawings.

Top left

: the gamine Fuegia Basket in England, aged 10.

Center right

: Jemmy Button around 1832, after several years of civilizing influence.

Center left

: Jemmy Button in 1834âFitzRoy believed even his cranium and features had improved in England, and then regressed again to primitive shape after just a year back in Tierra del Fuego.

Bottom

: York Minster as FitzRoy saw him at every stage, an intractable savage.

Top right

: Jemmy's wife in 1824. (Narrative of HMS

Adventure

and

Beagle, by Robert FitzRoy

)

The most fascinating aspect of these two portraits is that the Anglo Jemmy is dated 1833, the Savage, 1834, a year

after

Jemmy Button had been returned to Tierra del Fuego. FitzRoy chose to believe that such physical improvements lasted only as long as the heathen remained under the beneficent sway of God-fearing English culture. Once back in the wild, Jemmy's lips thickened, his nose widened, his brow bulged, his cranium reverted to its primordial shape.

FitzRoy's portait of York Minster in England shows a largely unimproved, thick-featured Fuegian with a tie and a haircut.

There was an immediate change in their living arrangements. Although FitzRoy later wrote that the Fuegians remained in Walthamstow until October of 1831, this was not the case. In August, the Reverend Wilson referred in a letter to their “late residence” there: FitzRoy had removed them. Where he put them, and to what degree Fuegia and York were separated, is not known.

But his urgency to leave England with them was real, and finally brought a change at the Admiralty. He confided his anxiety, and his plans to charter the

John,

to an uncle, the Duke of Grafton, who then interceded on his behalf. The duke, together with Beaufort, persuaded the Admiralty lords that FitzRoy's earlier survey

remained seriously incomplete: trade restrictions between Britain and the newly independent confederation of Latin American states had recently been lifted; French and American interests in the area rivaled and threatened to displace any possible British presence; a more complete survey of southern South American waters, plus the possibility of installing a group of friendly natives, perhaps under the auspices of the Church Missionary Society, could prove to be an incalculable political and economic opportunity.

Very quickly, FitzRoy was commissioned to embark on a new survey. He still had to pay most of the £1000 he had promised for the

John

, but now he had what he wanted: a chance to continue the work he had started, which was demanding and provided the best peacetime opportunity for him to shine as a naval officerâand the means to cut and run with the Fuegians.

Initially, he was appointed to the command of the

Chanticleer

, a near sistership to the

Beagle,

recently returned from a surveying voyage in South American waters, where her commander, Henry Foster, the Admiralty's leading field astronomer, had drowned in an accident on the Chagres River earlier in the year. But when examined, the

Chanticleer

was found to be too tired for such a voyage, her planking sprung, her gear and rigging worn out from her punishing travels in the Southern Ocean and the tropics. Another ship was quickly found; to FitzRoy's delight, it was the

Beagle

. He threw himself into preparations.

Â

The

Beagle

was commissioned anew on July 4, 1831, and

immediately given prime dock space at Devonport, and the work needed for a long and arduous period at sea commenced. With FitzRoy at the helm, Beaufort devised a much grander plan for this second voyage of the

Beagle

. In addition to the renewed survey of South American waters, he proposed that FitzRoy return to England by sailing westabout around the world, across the Pacific, through Australasia, across the China Sea and the Indian Ocean. This would enable FitzRoy to track an unbroken chain of

meridian distances around the world, which, depending on the accuracy of the chronometers carried with him, would enable the precise charting of the longitude of every port the

Beagle

called at. Much of the charting and surveying of the Pacific remained unimproved since Captain Cook's time, and this would be a significant opportunity to refine the mapping of the world, on which hung the expansionist improvements of trade, political power, and colonial possession. In addition, Beaufort and FitzRoy discussed a wide variety of botanical, geological, and meteorological inquiries that might be pursued on such a voyage, turning this circumnavigation into a showpiece of scientific endeavor. FitzRoy, the scientist-captain, was thrilled: “I resolved to spare neither expense nor trouble in making our little expedition as complete, with respect to material and preparation, as my means and exertions would allow, when supported by the considerate and satisfactory arrangements of the Admiralty.”

But beneath the exciting prospects, he also felt a gnawing concern. It would be a long voyage, several years at least, possibly three or four, during the whole of which he would be effectively alone, cut off from the world and even, especially, the men aboard his ship. FitzRoy was not a friendly commander, not an open-hearted Jack Aubrey or a matey Peter Blake. Although he had sailed and rowed and shared every hardship and success with his officers and men, he lacked ease with them. He was an aristocrat, high-strung, given to fits of depression and querulous anger. There would be no escape for him from the loneliness and isolation of command. This had driven Pringle Stokes, in whose cabin he would now spend years more, to shoot himself. There was madness in FitzRoy's own family which had resulted in the suicide of his uncle.