Read Folk Legends of Japan Online

Authors: Richard Dorson (Editor)

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Asian, #Japanese

Folk Legends of Japan (8 page)

Very strangely, a faint light began to glimmer in the direction of Kasaura. Genta thought this must be the sign of the god's mercy and he encouraged the boatmen to row as hard as possible to the light. So the boat arrived at Kasaura.

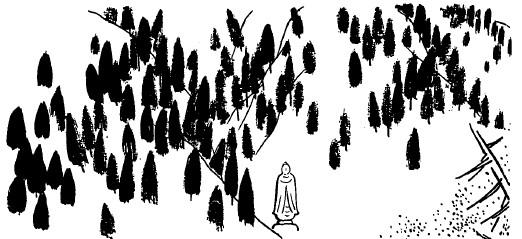

That night Genta climbed up the mountain, treading on the rocks and making his way through thorns. When he got to the top of the mountain, day began to dawn. He saw a pond on the mountain. As he was standing by the pond, a young woman appeared. Genta asked her: "Is there any god or man living on this mountain?" The girl answered: "Since ancient times no one has ever climbed this mountain. You are such a pious person that I have come here to ask you something."

Just then a young man suddenly appeared. This man and woman were the god and goddess of the mountain. The god lived in this pond and the goddess lived in another pond. But in the valley of this mountain lived the Buddha Yakushi, who should rightfully hold a higher place than these gods. So the gods said to Genta: "Please take Yakushi to the top of the mountain." And they took Genta to Yakushi and explained to him that Yakushi was formerly on the rock in the valley with the bodhisattva Miroku, but that Miroku was gone up to heaven. Genta asked them: "Where shall I install Yakushi?" "On the pond," said the gods. "But one cannot build a temple on a pond." "It does not matter, for we can make flat ground," answered the gods.

Just then a white bird flew away. They followed the bird down the valley. There stood a big rock on which was the statue of Yakushi. After Genta worshiped it, he went up the mountain again, carrying the statue. When he came to the pond, suddenly a thunderstorm broke out and the mountain peak collapsed and filled up the pond. Then the mountain gods appeared again and said: "This pond is called Daio-ike [Great King Pond] and the pond at the back of this mountain is Ryuoike [Dragon King Pond]. Now Daio-ike has been made into a flat ground, but Ryuo-ike will remain forever. If you suffer from the drought, pray for rain to this stone."

As soon as they finished these words, the two mountain gods disappeared.

Struck by a strange feeling, Genta was going to set the statue of Yakushi on the ground. The left knee of the statue was broken. Genta could not find anything to support the statue. He remembered the wooden pillow he always carried with him. He took it out and put it under the statue. Strange to say, it turned into a leg of the statue. As he was planting a sacred tree, the same white bird came flying there with ropes in its mouth, holding grasses in its claws. The bird placed these things before Genta. He made a hut with them.

Soon afterwards Genta went to Kyoto and visited St. Dengyo on Mt. Hiei to tell the whole story. Dengyo was moved by it; he gave him the name of High Priest Chigen and made him the founder of the temple.

PART TWO

MONSTERS

THE DEMONS of the Western world have by now become tame household possessions. We think of giants and ogres, goblins and sprites, and possibly unicorns and centaurs, as stock literary characters to entertain children. But in Japan the demons are still seen and talked about in the villages, and they take forms astonishing to the Western mind. The

kappa

appears ridiculous rather than monstrous, with his boyish form and saucer head, but his actions are far too lethal for comedy. The

kappa

has penetrated deeply into Japanese literature, art, and popular culture. The brilliant novelist Ryunosuke Akutagawa wrote a mordant satire,

Kappa,

in 1927, the year he committed suicide, about a man captured by and forced to live with

kappa.

Another distinguished writer, Ashihei Hino, launched his career by winning the Akutagawa Prize and has published a voluminous miscellany of

kappa

stories,

Kappa Mandara,

grafting modern personalities onto the goblin. A comic cartoon series by Kon Shimizu in the

Asahi Weekly

depicts a nuked kangaroo type

kappa

of lecherous and unseemly behavior. Coffeehouses portray

kappa

on their checks, and craftsmen shape him into wooden dolls. Almost equally infamous is the flying

tengu,

a beaked and winged old man, haunting the mountains as

kappa

infest the rivers, and abducting humans in the Noh and Kabuki of dramatists and

monogatari

of story-writers, as well as in the legends of the people.

Kappa

and

tengu

are not all bad and can teach healing and swordplay to human benefactors.

The

oni

is an ogre of Chinese origin, usually pictured with horns and fangs and a loincloth of tiger's fur. But to the primitive Japanese he was a friendly mountain giant who requited hospitality with faggots and stamped his footprints in mountain hollows. Other eerie monsters are found all over Japan, wild men of the mountains, apes in the sea, mischievous imps in the house, garden spiders that grow gigantic at night. And they are really seen, for the demons of Japan have not yet escaped from the folk to the pages of nursery books.

THE KAPPA OF FUKIURA

"The

kappa

is a fabulous creature of the rivers, ponds, lakes, and the sea," writes Shiojiri in his introduction to his translation of Akutagawas

Kappa.

Shiojiri goes on to quote from dictionaries and travel books of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries which describe the

kappa

as an ugly child with greenish-yellow skin, webbed fingers and toes, resembling a monkey with his long nose and round eyes, wearing a shell like a tortoise, fishy smelling, naked. He is said to live in the water and come out evenings to steal melons and cucumbers. He likes to wrestle, will rape women, sucks the blood of cows and horses through their anuses, and drags men and women into the water to pluck out their livers through their anuses. The trick on meeting a

kappa

is to make him spill the water in his concave head, whereupon he loses his strength.

Typical

kappa

legends, like the present one, deal with the creature's attempt to drag a cow or horse into a river. A comparative ethnological study of this theme showing similar accounts of water monsters in Asia and Europe, by Eiichiro Ishida, has been translated into English as "The Kappa Legend,"

Folklore Studies

(Peking, 1950), IX, pp. 1-152. The

Minzokugaku Jiten,

Joly (p. 161) and Mockjoya (I, pp. 196-98), all discuss

kappa.

Joly writes (p. 22) that kappa are usually propitiated by throwing cucumbers bearing the names and ages of one's family into the river. The contemporary vogue of

kappa

was described briery by Lewis Bush in the

Asahi Evening News,

Tokyo, May 29,1957, "The 'Kappa'

—

Japan's Goblin."

Ikeda,p. 43, suggests Type 47-C, "Water-monster captured, dragged by a horse" for the

kappa

traditions, and on the basis of her index Thompson has added Motif K1022.2.1, "Water-monster, trying to pull horse into water, is dragged to house where he begs for his life and is spared." Ikeda says that the affidavit given by the

kappa,

promising to do no more mischief, is treasured in some families.

Text from

Bungo Densetsu Shu,

pp. 76-77. Collected by Shizuka Otome.

I

N FORMER DAYS

a

kappa

often appeared to trouble the villagers of Fukiura in Nishi Nakaura-mura. One time the

kappa

came out of the river to the beach where a cow was tied to a tree. The

kappa

tried to insert his hand into the cow's anus and draw out its tongue. This startled the cow, which started to run round and round the tree, and in so doing caused its rope to wind round and round the

kappa's

arm. A farmer working in a nearby rice field noticed the

kappa's

plight and came running to the spot. Afraid of being caught by the farmer, the

kappa

tried to escape in such desperate haste that his arm, around which the rope was tightly wound, was pulled from his shoulder and fell to the ground. The farmer picked it up and carried it home.

That night the

kappa

called at the farmer's house and said: "Please give me back my arm that you took today. If you do not let me have it within the next three days, I cannot join it again to my shoulder." After imploring the farmer in this fashion he went away. The next night he came again, and the third night he appeared once more and repeated the same petition so piteously, with tears in his eyes, that the farmer felt sorry for him. He said: "Will you promise us that you will never do harm to the villagers, either the children or the adults? I will give you back your arm if you will keep your promise until the buttocks of the stone Jizo over there rot away."

The

kappa

made this promise to the farmer, and in consequence was able to depart with his arm. After that he went to the stone Jizo every night and examined its buttocks to see if they were rotted, but they showed no sign of going bad. He sprinkled excrement on the Jizo, but still it failed to rot, and the

kappa

at last grew disappointed and gave up all further attempts.