Read Fractions = Trouble! Online

Authors: Claudia Mills

Fractions = Trouble! (2 page)

After school Wilson met Kipper outside the kindergarten room so they could walk home together.

“Guess what?” Kipper shouted as soon as he saw Wilson.

Wilson shrugged. He wasn't in the mood for guessing, especially if the guess had anything to do with Peck-Peck and Snappy, each clutched in one of Kipper's hands.

“You know how you and Josh were

talking about the science fair when Mom and I got home from our bike ride on Saturday?”

talking about the science fair when Mom and I got home from our bike ride on Saturday?”

“Yeah. What about it?”

“My class is going to do the science fair, too!”

“So?”

“So

I'm

going to have a science fair project! With one of those big white boards that folds up, with pictures and words all over it! Our parents can help with the writing part, Mrs. Macky said. Brothers and sisters can help.

You

can help!”

I'm

going to have a science fair project! With one of those big white boards that folds up, with pictures and words all over it! Our parents can help with the writing part, Mrs. Macky said. Brothers and sisters can help.

You

can help!”

Hooray,

Wilson thought glumly.

Wilson thought glumly.

“Andâwhat's the long, hard word that starts with

H

?

Hippopotamus

?”

H

?

Hippopotamus

?”

“Hypothesis.”

“I'm going to have a hypothesis!”

Wilson gave in and returned Kipper's huge grin. It was great, in a way, how little

kids could still be so excited about everything. And no little kid was ever more excited than Kipper.

kids could still be so excited about everything. And no little kid was ever more excited than Kipper.

Â

Wilson felt a lot less like grinning on Wednesday afternoon when he and his mother, Kipper, Peck-Peck, and Snappy set out to walk to Mrs. Tucker's house for his first day of math tutoring.

“You don't have to walk with me,” Wilson objected. “It's only a few blocks.”

“I want to go with you today,” his mother said. “At least for your first session. To make sure you find Mrs. Tucker's house and to introduce you to each other.”

Wilson sighed. He didn't mind so much that his mother was coming with him; he minded that Kipper was coming with himâKipper

and

Snappy

and

Peck-Peck. But of course Kipper was too young to be left at

home alone. Instead, Kipper would show off, and make Snappy and Peck-Peck talk about fractions, and Mrs. Tucker would think how cute Kipper was, and how smart. And how un-cute Wilson was, and how dumb.

and

Snappy

and

Peck-Peck. But of course Kipper was too young to be left at

home alone. Instead, Kipper would show off, and make Snappy and Peck-Peck talk about fractions, and Mrs. Tucker would think how cute Kipper was, and how smart. And how un-cute Wilson was, and how dumb.

Luckily, when they reached Mrs. Tucker's houseâa yellow house with bright blue shutters and hundreds of daffodils in bloomâWilson's mother told Kipper to wait quietly.

“I want to talk to the math tutor!” Kipper whined.

Their mother silenced Kipper with a glance.

Wilson wasn't sure what a math tutor would look like. When she opened the door, Mrs. Tucker turned out to be a small, birdlike woman, hardly taller than Wilson. She was as colorful as her house, wearing a long purple skirt, a yellow sweater, and red and blue glass beads. At least she wasn't wearing earrings shaped like numbers, or a sweatshirt with equations on it.

Wilson's mother presented him to Mrs. Tucker, handed her a check, gave Wilson a quick hug, and left with Kipper.

Wilson wished he could go with them.

“Come on in!” Mrs. Tucker said.

Wilson did.

Mrs. Tucker led Wilson to a room off her kitchen. In it was a table and chairs, like the table and chairs in Wilson's classroom. A low bookshelf held lots of books, probably all boring books about math. But then Wilson recognized a couple of the titles:

Charlotte's Web

and one of the Harry Potter books.

Charlotte's Web

and one of the Harry Potter books.

“So,” Mrs. Tucker said, once Wilson was

seated at the table. “Your mother said you need some help with fractions.”

seated at the table. “Your mother said you need some help with fractions.”

“I guess so.” He needed help eliminating fractions from the planet.

The thought made him smile, and Mrs. Tucker said, “What?”

“Nothing.”

“Come on, tell me. You just thought of something funny. If we're going to be spending two hours a week together, we might as well share anything funny.”

Two

hours a week? Wilson had thought he was coming

once

a week. But so far Mrs. Tucker was nice, so he told her about eliminating fractions from the planet.

hours a week? Wilson had thought he was coming

once

a week. But so far Mrs. Tucker was nice, so he told her about eliminating fractions from the planet.

She laughed. “All right. Poof! All fractions are gone! If you ruled the world, what would there be instead of fractions?”

“Drawing. And hamsters.”

“Do you have a hamster?”

Wilson told her about Pip and Squiggles.

“Great! Once I had two hamsters, named Twitchell and Boo-Boo.”

Mrs. Tucker pulled out a large sheet of paper and three tubs, one of markers, one of crayons, and one of colored pencils.

“Draw me some hamsters,” she said. “Draw me four hamsters.”

Wilson stared at her. He knew his mother wasn't paying Mrs. Tucker so that he could sit at Mrs. Tucker's house drawing hamsters. He could sit drawing hamsters at home for free. But he wasn't about to complain and beg to do fractions instead.

And pretty soon he was doing fractions, sort of.

Pip was ¼ of the group of four hamsters.

Squiggles and Pip together were

of the group of four hamsters.

of the group of four hamsters.

of the group of four hamsters.

of the group of four hamsters.Twitchell was ¼ of the group.

Twitchell and Boo-Boo together were

of the group.

of the group.

of the group.

of the group.When the hour was over, Wilson had filled four large sheets of paper with hamster drawings, and Mrs. Tucker had never once used the words

numerator

or

denominator

.

numerator

or

denominator

.

Wilson had to admit it hadn't been as bad as he had thought it would be. But

numerator

and

denominator

had to be coming. Mrs. Porter's test wasn't going to be a hamster-drawing test, where kids passed if they could draw ten hamsters in fifteen minutes. At school they were even starting to add fractions together. With Wilson's luck, soon they'd be subtracting fractions, and multiplying fractions, and dividing fractions. Wilson would still be the only kid who couldn't do it, however many hamsters he drew.

numerator

and

denominator

had to be coming. Mrs. Porter's test wasn't going to be a hamster-drawing test, where kids passed if they could draw ten hamsters in fifteen minutes. At school they were even starting to add fractions together. With Wilson's luck, soon they'd be subtracting fractions, and multiplying fractions, and dividing fractions. Wilson would still be the only kid who couldn't do it, however many hamsters he drew.

“Do you want to take your pictures

home, or may I keep them?” Mrs. Tucker asked as Wilson stood up to leave.

home, or may I keep them?” Mrs. Tucker asked as Wilson stood up to leave.

Wilson hesitated. It would be cool to have the pictures for his room. But Laura and Becca both lived nearby. Wilson imagined seeing them on their bikesâkids who didn't go to math tutors had time to ride bikes after school. They would see his rolled-up sheets of paper, and one of them would say, “What are those, Wilson?” And he'd say, “Oh, those are the hamsters I drew with my math tutor.” And they'd say, “What? You have a math tutor?”

Wilson shook his head.

“You can keep them,” he said.

“How did it go?” Wilson's mother asked when he walked in the door.

“Okay.” He wasn't going to tell her that he had spent the whole time drawing hamsters. She might fire Mrs. Tucker and get him a different math tutor who would make him spend the whole time doing math.

Fortunately, his mom didn't ask anything else, though Wilson could tell she wanted to. He hated seeing the hopeful

look on her face, as if one hour with a math tutor would have solved her son's problems with fractions forever.

look on her face, as if one hour with a math tutor would have solved her son's problems with fractions forever.

“She said I'm going to be seeing her

two

hours a week,” Wilson said. “I thought I only had to go

one

hour a week.”

two

hours a week,” Wilson said. “I thought I only had to go

one

hour a week.”

“No, it's going to be twice a week, on Wednesday afternoon and Saturday morning. We're lucky that Mrs. Tucker had these openings in her schedule.”

Lucky

wasn't the word Wilson would have chosen.

wasn't the word Wilson would have chosen.

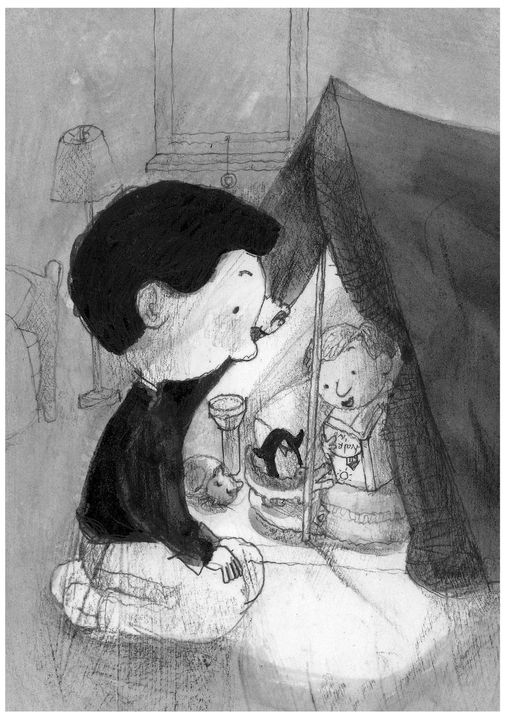

Pip wasn't in her cage in Wilson's room. He found her in Kipper's room. Or rather, he found her inside the tent in Kipper's room.

Since their overnight family camping trip one weekend during spring break, Kipper had been sleeping every night in the small tent he had begged his parents

to set up in his bedroom. Wilson couldn't decide if the tent was cool, or stupid. Maybe cool in a stupid sort of way. Or stupid in a cool sort of way.

to set up in his bedroom. Wilson couldn't decide if the tent was cool, or stupid. Maybe cool in a stupid sort of way. Or stupid in a cool sort of way.

Inside the tent Kipper was reading a story to Pip, Peck-Peck, and Snappy. The only problem was that Kipper couldn't read. So he was holding the book and making up his own story, about three friends named Pip, Peck-Peck, and Snappy.

Wilson crawled inside the tent and picked up Pip, who had been dozing in a tightly curled little ball.

“And they lived happily ever after,” Kipper finished quickly. “What is your science fair project going to be?” he asked Wilson.

“I don't know.” Josh's popcorn-catching idea was funny, but Wilson didn't feel like finding a whole bunch of kids and grownups and dogs and cats who were willing to let him test how many kernels of popcorn they could catch in their mouths. He doubted that even his own parents would agree to do it.

He stroked Pip's firm little body, feeling the gentle rise and fall of her breathing. Maybe he could time how many hours a day she slept versus how many hours a day she ran in her wheel. Or he could teach her to do tricks, to see how smart she was. He could probably teach her to do some amazing tricks.

“Actually,” Wilson said, “I'm going to do experiments with Pip.”

Kipper's face lit up. “Can I do experiments with Pip, too? Pip is my hamster, too!”

“No!” Wilson hated that Pip was Kipper's hamster, too. Kipper already had Peck-Peck and Snappy. Why did he need half of a

hamster? Half of

Wilson's

hamster. “Think of your own idea.”

hamster? Half of

Wilson's

hamster. “Think of your own idea.”

Kipper pushed out his lower lip: step one of Kipper crying.

Kipper's eyes started to water: step two of Kipper crying.

Before Kipper's mouth could start to trembleâstep three of Kipper cryingâWilson said, “I'll help you think of another idea, an even better idea.”

“Like what?”

Good question. Nothing was better than doing experiments with hamsters. Wilson looked around, desperate for inspiration.

“Likeâsomething about tents.”

“Like what about tents?”

At least Kipper's mouth wasn't trembling and his eyes had stopped watering. His lip still stuck out, though.

“We'll ask Dad when he comes home.”

Their dad loved anything to do with camping. If anyone could think of a good science fair project about tents, he would be the one.

Wilson crawled back out of the tent with Pip, soon to be co-winner of the Nobel Prize in Science Fairs.

Â

“Tents,” their father said as he speared the first meatball on top of his spaghetti.

“We could set up all our tents”âtheir family owned threeâ“and see which tent is the biggest,” Kipper suggested.

That didn't seem, to Wilson, like the right kind of question for a science fair project. Which person in their family was the tallest? Their dad. Which person was the shortest? Kipper. Or Pip, if she counted as a person. It was too easy. But he didn't say anything, for fear that his father

would change the subject and start asking him about his math tutoring.

would change the subject and start asking him about his math tutoring.

“Let's think a bit more,” his dad said. “What do we want a tent for?”

“To keep out bears!” Kipper made Peck-Peck and Snappy jerk their heads with fear of bears. Peck-Peck and Snappy sat at the table every night for dinner, while Pip ate alone in her cage. It was another thing in Wilson's life that wasn't fair.

“Well, a tent won't provide much protection from bears. But it definitely helps with rain and wind. All three of our tents are waterproof, but I know from experience that some tents do better in the wind than others, depending on their size and shape. We have one big, tall tent, and one small, low tentâthat's the one in your room, Kipperâand a medium-sized one. How about setting up all three tents outside in the backyard on a windy night and

seeing which one holds up best in the wind?”

seeing which one holds up best in the wind?”

“I think the big one will be the best,” Kipper said.

Their father looked as if he thought that was the wrong answer, but didn't want to come right out and say it. “Okay, boysâWilson, you can help with this, too. Think about a sailboat. Which sail would catch more wind: a big, tall one or a little, low one?”

“The big one,” Wilson said. That seemed obvious.

“Yes,” their dad said. “But when it comes to tents, you

don't

want them to catch the wind, right? So that means that, in the windâ”

don't

want them to catch the wind, right? So that means that, in the windâ”

“A little one would be better,” Wilson said, since Kipper had obviously stopped listening to their dad's explanation.

Kipper's face lit up with a new idea. “Can

we put Peck-Peck and Snappy in the tents when we test them?”

we put Peck-Peck and Snappy in the tents when we test them?”

“I don't see why not,” their dad said. “And then we can find out whether a small, low tent really is better for camping in the wind.”

“Boys, you need to let your father eat his supper,” their mother said. As if Wilson had said or done a single thing so far to distract anybody from eating anything. “Wilson, have you come up with an idea for your project?”

“I'm going to teach tricks to Pip and see how long it takes her to learn them.”

“When is the science fair?” his dad asked, swallowing another meatball.

“In two and a half weeks. On a Friday.” The same day as the big horrible fractions test. If only Wilson could pass that test and never have to go to a math tutor again.

“Good luck,” his dad said. He made it sound as if two and a half weeks wasn't going to be enough time. Well, his dad might know a lot about tents and sailboats, but this showed how little he knew about hamsters.

“May I be excused?” Wilson asked.

“Your dad is still eating,” his mother said.

“Just let him go,” his dad said.

As Wilson was heading away from the table, his father called after him, “Oh, Wilson? I forgot to ask: what happened with the math tutor today?”

Wilson pretended that he hadn't heard. Off he raced to start training Pip.

Other books

An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy 1917-1963 by Robert Dallek

The Astrologer by Scott G.F. Bailey

Faces of the Gone: A Mystery by Brad Parks

Masks by Fumiko Enchi

The Misfits by James Howe

The Curvy Voice Coach and the Billionaire Actor (He Wanted Me Pregnant!) by Victoria Wessex

Courting Holly by Lynn A. Coleman

Frosted by Allison Brennan, Laura Griffin

Broken Road Café 1 - The Broken Road Café by T.A. Webb

Lone Wolf Pack 04.1 - Bonded to His Werewolf Lover by Anya Byrne