Las Christmas (10 page)

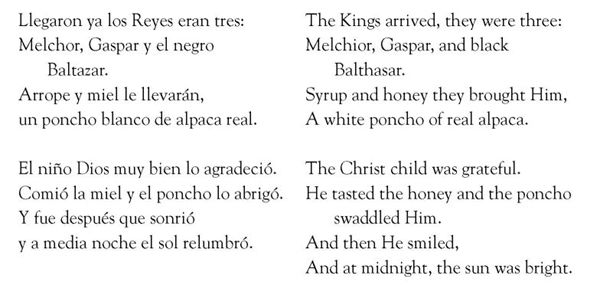

LLEGARON YA LOS REYES

An Argentine Folk Song

Argentine Matambre

FLANK STEAK ROLL

Knowing that Estela Herrera is a great cook, we begged her to give us this recipe for the

matambre

she mentions in her story.

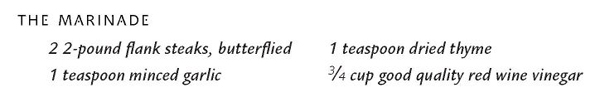

Marinate steak one day in advance:

Trim away all gristle and fat from the meat. Lay one steak, cut side up, on a non-reactive 12 Ã 18-inch pan. Sprinkle it with half the vinegar, half the garlic, and half the thyme. Place the second steak on top and repeat the process. Cover the pan and refrigerate overnight.

Wash and trim the spinach or chard. Discard the stems and blanch the leaves.

In a small frying pan, heat the oil and cook the sliced onions slowly until translucent (about 10 minutes).

Lay the steak end to end, seasoned side up, overlapping them about 2 inches. Pound the joined ends together to seal securely. Spread the spinach leaves evenly over the meat and place the carrots on top, laying them in a parallel row along the length of the meat, across the grain. Arrange the eggs on top and scatter the onion rings. Sprinkle the entire surface with the parsley, chili and salt.

Carefully roll the steaks along the grain into a long, thick cylinder. Using a 10-foot-long piece of cotton twine, tie one end around the roll about 1 inch from the end and knot securely. Holding the twine in a loop near the knot, wrap the remaining length around the steaks about 2 inches from the edge of the roll and feed it through the loop. Pull the twine tight to keep the loop in place. Repeat until the roll is completely tied in loops at 1-inch intervals, then bring the remaining twine across the bottom of the roll to the first loop and tie it securely.

Preheat the oven to 375 degrees.

Place the steak roll (

matambre

) in a casserole or roasting pan big enough to hold the meat snugly. Pour the stock over it, adding enough water to cover the roll entirely. Cover the pan tightly and place in the middle of the oven for 1 hour. Remove the roll from the pot onto a cutting board or platter and place the weights on top, allowing the juices to drain off for about 5 hours. Refrigerate until cold. Serve thin slices as a cold hors d'oeuvre accompanied by a green salad.

Makes

10

to

12

servings

Gary Soto

Gary Soto grew up in Fresno, California. He has written twenty-seven books

for adults and young people,

including

Baseball in April

(Harcourt Brace),

Living up the Street

(Dell),

Too Many Tamales,

and

Chato's Kitchen

(both from Putnam). He lives with his family in Berkeley, California.

ORANGES AND THE CHRISTMAS DOG

FOR CHILDREN, Christmas means the arrival of gifts. At age ten in sloppy clothes and misshapen clown's shoes, I wanted my share. I was greedy for something, anything, even the oranges and pens my stepfather's mother pressed into our arms. My brothers and I could have hopped the fence and gotten free oranges from our neighbors. But I figured why make a face about an expected gift, especially since my stepfatherâ drunk in his recliner, his head hovering over a TV tray stamped with dead presidentsâwould have bellowed about our ungratefulness.

Children expect gifts, and if Baby Jesus shows up, that's fine, too. As a Catholic fourth grader at St. John's Elementary School, worried for the poor and the children of Biafra, I wanted Baby Jesus to be born, swaddled, sung to, adored, celebrated . . . all that. But thenâand I'm sorry to say thisâI just wanted to get my presents. That year I ruined all the expectation of Christmas by tearing tiny holes in the wrapping of my three gifts. With the roving eye of a surgeon examining stomach guts, I probed into the bright wrapping. In the box there was a jigsaw puzzle, in another a sweater, in the third a rifle. I could see that the rifle didn't cock like the more expensive toy rifles, the kind the rich kids would get. Mine was just a length of hard plastic to point at my neighbor Johnny or my little brother, Jimmy, or even my own head, and sputter, “

Tutututututu,

you're dead!”

My older brother, Rick, was outside trying to kill time until Christmas, which was two days away, a slow drip of minutes like a leaky faucet. He had to do something to keep his mind off the presents.

“I know what I got,” I told Rick as I walked toward him on the frost-hard lawn. In fog-shrouded Fresno, the neighborhood of ancient houses was dead. Only kids or really dumb people would venture into that chilling scene. Maybe we were both.

“You peeked, huh?” he said. He was eating free oranges from the neighbor's house. “You stupid!” He knew that I had wrecked my happiness. Now I would have to wait an entire year, until next Christmas, before that overwhelming yearning for presents possessed me again.

“I got a rifle,” I mumbled.

“I picked it out,” Rick said.

“You're lying.”

“It's a green rifle.” The final slice of his orange went into his mouth.

Then I thought that maybe this mean brother of mine did pick it out, and had chosen a cheap one so that Mom could buy him better presents. I felt angry as a ferret. My breath shaped into a fist in front of my face. But before I could act on my anger, the neighbor's shamefully underfed dog walked over. His fur was like the dirty carpet under an overturned chair. Without a collar or the tinny chime of dog tags, the mutt appeared naked. His ribs clearly showed.

“Watch this.” Rick pulled an orange from his jacket and clawed it. He peeled off a slice and fed it to the dog.

“He likes 'em,” he said.

The dog closed his mouth around the orange slice, letting it rest there for a moment. As his furry chin began to churn, a trail of juice leaked from his mouth.

Poor dog, I thought, he's really hungry. I took the orange from Rick and dug my fingers into it, then held out a piece. The dog took a step on the frosty lawn. I wondered if his paws were cold without any shoes. Once I had walked barefoot from the house to the car to get a comic book. Those thirty or so steps hurt. I couldn't imagine having to walk on frost all winter.

Rick left. The dog raised his watery eyes to mine. A groan issued from the cave of his lungs.

“Don't go away,” I told the mutt. I dashed into the house and threw open the refrigerator. Wasn't a starving dog an emergency? I pulled open the meat drawer and eyed the bologna, my stepfather's precious lunch. I carefully peeled off a single slice, set it on a piece of bread, and covered it with a second piece. But in my hand, the sandwich lacked the weight that might fill in a starving dog's ribs. Again I scanned the meat drawer: a chunk of hard yellow cheese. I broke the cheese into crumbs and sprinkled it on the sandwich. I considered spanking the bread with mayonnaise, then reconsidered, and hurried outside.

“Hey,” I called. The dog had walked partway up the street. He turned his head slowly, then his body, and sat down, paws together. I hurried to him.

“You need to eat,” I told him. I shoved the sandwich at his mouth. His nose, black as oil but dry as a leaf, sucked in the smells. He sniffed, then took a small bite. I figured he was so hungry, so tired, that he would eat it slowly, one little bite at a time.

“You're going to be okay,” I told him, my hand riffling through his matted fur. He finished the sandwich and I went back inside for milk. What could be better than milk to wash down a sandwich? It took a while to find something other than a cereal bowl. It would bring on Mom's wrath if she found out I was feeding a dog from our dishes. I returned with a soup can brimming with milk. I had to walk slowly, one careful step at a time, the frost crunching like bones under my shoes.

“Where are you?” I called to the dog, who had moved further down the street to Mrs. Prince's house. “You like milk, don't you?” I asked as I got closer.

The dog didn't reply with a bark. He didn't appear any friskier from the sandwich or relieved that someone was concerned. I thought that maybe he would see me as a savior. Wasn't it nearly Christmas? He looked at me with watery eyes, his sadness as ancient as the Nile.

I poked the can under his nose. He sniffed its contents. I poured milk, splash by splash, into my palm and let my new friend quench his winter thirst until his snout was nearly drowned in milk.

“That's good, huh?”

The dog turned away, done with me, fed but maybe unsatisfied, his lifeless tail like a shoestring. I placed the can on the curb intending to pick it up later. But I heard a tap-tap on a window: Mrs. Prince had parted her curtain and shook a finger at me. I waved and picked up the can. I chased after the dog, who loped like a burro, with a slow, clip-clop action of hooves.

We stopped at the corner of Angus and Thomas. The streets were dead in the cold, metal-gray afternoon. The sun would not reach us that day.

“Where do you want to go?” I asked.

The dog looked straight ahead. Then, like a zombie, he crossed the street. I followed, pressing him, “Where are you going? Huh? You're going to get lost!”

I remembered from somewhereâa nature program like

Wild Kingdom?â

that a sick elephant left the herd when it knew it was dying. I was scared. Was this dog pacing out the distance from our block to where he would finally roll on his side, kick his paws into the air, and die?

“You ain't sick, are you?”

I stopped him by hugging him around his neck, warm as blankets. I looked him straight in the eye, my own face appearing on the surface of his wet eyeballs. That scared me even more. I was suddenly part of this dog's life, a picture on the windows of his soul. I knew that animals didn't have souls, or so the nuns taught, but I could see, however briefly, that my presence held meaning for this dog. His tail began to wag.

I rubbed his back, building up the heat of friction. I patted him and ran my hand over his head, slendering his eyes. Two more teary drops leaked away the picture of my face.

“Let's go back home.” If I had been meaner, I would have cursed the owners of this dog, a family of renters who had shown up one day. They lived two houses from us, and we were told to stay away from the three sickly kids with broomstick bodies. My mother thought they might have TB.

“Come on,” I begged the dog. “Let's go back. I got another sandwich for you.”

I turned him around and pushed and prodded him to return to our block, which had nearly disappeared in the fog. It looked unfamiliar, like an altogether different town, with different people, different cars, and if the doors were flung open, a whole set of kids I didn't know.

I walked alongside the dog, whose pace had quickened, as if he were in a hurry. Had he been human, he might have looked at the watch on his wrist. He started to run, not fast but fast enough that I threw the soup can to the curb and broke into a jog. I couldn't worry about littering.

“You're going to get lost!”

The dog cut erratically across lawns and into the street, heedless of the occasional cars, sinister headlights frisking the leaf-strewn street. He slowed for a moment, then trotted up someone's lawn and onto the porch. I didn't dare climb the steps. My mom always warned us to stay out of other people's yards, advice I usually ignored on my block. But here, in this strange place, I stayed on the sidewalk. I was cold. My nose was red and I jumped from foot to foot.

“Come on,” I whispered to the dog on the porch. He sat only a brief moment and then climbed down the steps and made his way to the backyard. He acted as if he belonged there, the family pet instead of a stray.

“No! Don't go over there!” I yelled.

The dog didn't look back. I thought he was on his way to his grave, the place to lie down in fog. And when the fog cleared, he would be gone. I stood on the sidewalk, not sure what to do. A giant sycamore dripped water on me. Cold worked into my bones. I rubbed my hands together, gathering up heat, waiting for him to reappear. As I stood there, I recalled how in second grade I had asked my mom if there was a chance that one day I might become a saint. I had just returned home from St. John's Elementary and I wanted more than anything to be holy by feeling for the poor, who were so plentiful. I don't remember her answer.

I figured here was my chance to approach sainthood, my chance to walk alongside the dog until it was time for him to die. I must have waited on the curb, freezing, for two hours. Finally, I eventually ventured into the backyard, whispering, “Come on, boy. Come on!”

I raised my eyes to the windows. At any moment a large man would come out yelling for me to go away. He would have a gun or a stick to whack sense into me. That's when I discovered that not only was the dog gone, but I was no saint because I was ready to give up so soon. I felt ashamed, then mad. When I returned home, the dog was back on his porch. He had cut through the yard, leaving me standing in the cold.

“You're bad,” I scolded the dog, who didn't even seem to recognize me. He sat among orange peels and ripped-up newspaper. One of the broomstick kids came out. His skin was nearly transparent, and his eyes were sunken.

“Leave my dog alone,” the kid said.

I did. I returned home, stiff from the cold. After I stood over the floor furnace, I wandered into the kitchen. It was 4:30 and dark outside. A few orange porchlights cut through the fog. The dark descended on us. Soon Mom was home from work, followed by our stepfather, who took his place in his recliner, the TV coloring the walls. After dinner, Pearl showed up with gifts of pens and oranges. Christmas was two days away, but we were allowed to open one present each. Pearl looked on, face heavily rouged, smiling and hoping that we would pick hers. And we did. I tore into that poorly wrapped present and smiled up at her, for wasn't it Christmas, a time to be appreciative, like a dog? I dug my fingernails into the oranges. Their mist and scent atomized that moment when I knew that I was no saint. I fit not one but five slices into my mouth. I chewed, churned the juicy pulp, and swallowed for Pearl, such a happy woman, who waited for me to clear my throat and say once again, “Thanks, Pearl, these oranges are really, really good.”