Read Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures Online

Authors: Sir Roger Moore Alec Mills

Shooting 007: And Other Celluloid Adventures (8 page)

Although I shower praise on my champion, the problem of Harry’s short temper, which first came to light on

The Sleeping Tiger

, would remain in the background. At the time I had thought that Harry’s outburst with Joe Losey was a one-off, an unfortunate moment of folly which would never happen again. It was not, but even this problem could not change my loyalty to the guv, though it would be necessary to understand him and stay alert to his ever-changing moods.

For the record, I remained Harry’s camera assistant for nine years from 1952 to 1961, working on productions including

The Sleeping Tiger

,

Father Brown

,

Lost

,

Contraband Spain

,

House of Secrets, Robbery Under Arms, Third Man on the Mountain

and finally

The Roman Spring of Mrs Stone

.

Fate dealt me a good hand when I met up with Harry Waxman BSC.

Earlier, I mentioned the problem I had in writing of friends and colleagues, knowing that this would not always tally easily with the challenge of telling the truth – at least the truth as I see it. Writing an autobiography makes it necessary to camouflage an account here and there, so take what you will from this private account.

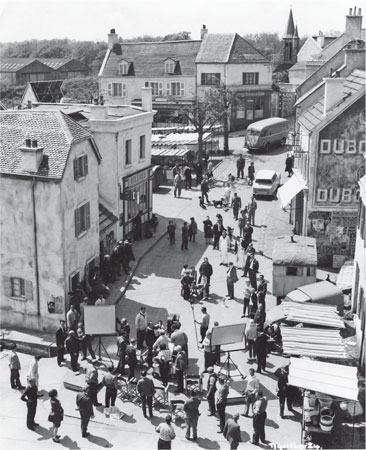

Pressing on and hoping not to cause offence, unlike the Losey affair, Harry’s next film would be a pleasant experience, with Alec Guinness playing the title role of

Father Brown,

a kindly priest-cum-amateur sleuth. In the film, Father Brown tracks down Flambeau (Peter Finch), a well-to-do thief who stole a famous cross from the priest’s church. It is a wonderful tale with an interesting script, the interplay between priest and thief becomes a challenge for the minister as he sets out to reform the criminal. Our location filming would take the unit to Paris and Cluny, a small wine-growing town hidden somewhere in the countryside. It was a taste of wonderful things to come. More important, Paris was my first experience of foreign travel, so it was necessary to further my education with a visit to the Folies Bergère, with my graduation taking place at the Moulin Rouge, where one could appreciate the female form.

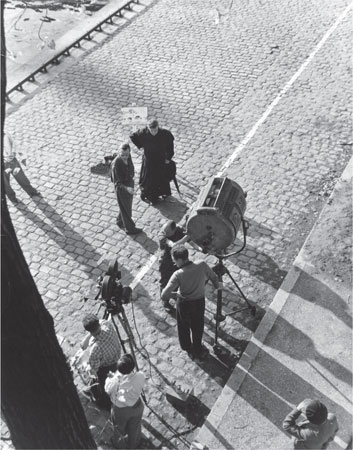

On location in France with

Father Brown

in 1954. Alec Guinness, leaning on an umbrella, plays the lead role of God’s detective, discussing a scene with director Robert Hamer. I am the camera assistant standing behind the camera operator. The big lamp, known as an ‘arc’ lamp, housed carbon rods with negative and positive poles, creating an ‘arc’ of light when the lamp was switched on. The carbons had to be adjusted from time to time as they burned down, before they were eventually changed, a process that could take up to ten minutes per lamp.

With a happy relaxed atmosphere on the set I became interested in the director’s role. I suddenly realised that I had an enquiring mind which had somehow been hidden during my schooling years; it would seem that I was becoming more inquisitive. This miracle came about while listening in to a low-key conversation between the director Robert Hamer and Alec Guinness, discussing the scene while the set was being lit.

On

Father Brown

the bright French sun meant that very often a simple reflector would suffice to light the scene, with only a few reflectors being needed overall.

Standing close to my camera, where the camera assistant normally exists – my domain – made it impossible not to eavesdrop on their discreet conversation. I became intrigued by the actor’s reading of the scene, or – dare I say – his confusion. This humble nonentity had the impertinence to listen in and had a silent opinion of his own; they didn’t ask and I didn’t tell.

I listened and took note of the skills of good directing, where the director’s authority faces the challenge of doubting actors. With Harry’s advice to ‘look, listen and observe’, I found myself totally absorbed with the director’s approach to what he required from the scene, his sensitive timing. The actors’ concerns were politely listened to and then they found themselves playing the scene – more often than not in the director’s preferred way. I believe this was when I first began to understand what made a good director: in part it is his relationship with actors and, if necessary, an ability to gently disarm the overconfident performer who had other ideas of how the scene should be played.

Of course, it goes deeper than that, but in the unlikely event that I would ever achieve status as a director I would probably model myself on a gentleman by the name of José Quintero, a director who in the future would make a big impression on me, as did Roman Polanski’s directing of

The Tragedy

of Macbeth.

Alec Guinness, Joan Greenwood and Cecil Parker had no problems with Robert Hamer’s ability, having worked with the director before during their Ealing Studio days; nor would Bernard Lee, Sid James or Peter Finch.

Harry was very excited about his next film, where he would be working with the Oscar-winning cinematographer Guy Green. Guy had won the award for his black-and-white cinematography (in those days there were separate prizes for colour and black-and-white films) on David Lean’s

Great Expectations.

Other images by Guy which will stay long in British cinema history are

Oliver Twist, Captain Horatio Hornblower

and

The Way Ahead,

to name but a few.

Lost

was the story of a baby who disappears from his pram, with Inspector Craig (David Farrar) setting out to find the child with few clues to go on; David Knight and Julia Arnall played the stricken parents while Thora Hird contributed to the drama.

Guy would be the director of

Lost,

with Harry Waxman his preferred cinematographer. It was a partnership which created much discussion within the filming community as two respected cinematographers would be working closely together. Harry sang loud in praise of Guy’s work; he was excited about this new partnership. If truth be told, I could hardly wait to meet this highly respected gentleman: he had a reputation for being quiet and polite to all. At the same time, I wondered if I should be concerned about the different opinions that they might have – another

Sleeping Tiger

for Harry …

Guy Green now arrived wearing a different hat and with different responsibilities resulting from the many pressures put on a director due to production demands, not least with scheduling. Directors are not alone in this problem: cinematographers also get tangled up in these situations when schedules start to slip, resulting in the sacrifice of creative art in favour of speed, which I suggest was the situation on

Lost

.

One day as we approached lunch Guy was clearly behind on the day’s dreaded call sheet. The pressure was slowly building, with the director hoping to complete the sequence before the break in order to stay on schedule. Guy’s unease was no help to Harry, who was feeling the pressure the director was putting on him. Past experience suggested that this rolling snowball was now fast approaching. With the clock ticking, the director’s frustration was clear for all to see, as was his cinematographer’s; his face was starting to redden – a sure sign from past experience that Harry was close to exploding and speaking his mind about all the pressure Guy was putting on him. Even so, Harry held his peace and I quietly prayed to myself, knowing that the scene could not possibly be completed before the lunch break. In spite of this the director tried once more, pleading to a fellow cinematographer.

‘Harry, just light it, please!’

I closed my eyes, holding my breath as I listened to this sudden increase in the level of Guy’s appeal. The set went quiet. It was as if all sound had been switched off as we waited on Harry’s reaction. It had to come – this had not been a gentle tone from the Guy Green we all loved and respected. To be honest, Guy’s remark was unfair to a fellow cinematographer who was doing his utmost to meet Guy’s deadline; with my past experience of Harry and Joe Losey’s encounter I waited nervously for Harry’s likely response to Guy’s unfortunate lack of tact.

Harry’s face now moved from red to crimson, confirming my assessment that the volcano was close to erupting. However, this time the expected outburst would be different – controlled and extremely professional. The cinematographer looked at the director firmly, quietly reminding him that as a cinematographer at no time in his illustrious career did he ‘just light’ his artistes or his sets; with that we broke for lunch.

After that stand-off I was left speechless at Harry’s discretion, unsure whether to praise his diplomacy or to be wounded at Guy’s unwelcome proposal to a friend and colleague. I played it safe, calling it a draw. To his credit, Harry’s wise control saved the incident from getting out of hand and prevented a cloud forming over his relationship with Guy, whom he truly respected. For the record, they did get on well together. No doubt Guy felt uncomfortable with his comment in the first place, undoubtedly sparked off by the insane pressures put on directors and cinematographers which can be difficult to accept. Again, one might ask, would the film suffer as a consequence of ‘just lighting it’? Of course it would; my money would be on Harry this time.

Cinematographers are aware of their responsibilities and what the photography adds to the drama and how it helps the storyline. The ‘look’ of the film is discussed between director and cinematographer before filming takes place and if that look or other creative elements are sacrificed then the plan slowly starts to diminish. So now I wondered how I would react should a challenge be placed on me in that same manner. To be honest, I really did not know, but again there would always be something new to learn from in this dream world where I existed. No doubt time would tell …