Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (9 page)

Although it is impossible to prove it, one suspects that these various general features related to one another, by some inner logic as it were, and that all were necessary. It was a combination of economic laissez-faire, political and military pluralism, and intellectual liberty—however rudimentary each factor was compared with later ages—which had been in constant interaction to produce the “European miracle.” Since the miracle was historically unique, it seems plausible to assume that only a replication of all its component parts could have produced a similar result elsewhere. Because that mix of critical ingredients did not exist in Ming China, or in the Muslim empires of the Middle East and Asia, or in any other of the societies examined above, they appeared to stand still while Europe advanced to the center of the world stage.

*

For a brief while, in the 1590s, a somewhat revived Chinese coastal fleet helped the Koreans to resist two Japanese invasion attempts; but even this rump of the Ming navy declined thereafter.

The Habsburg Bid for Mastery, 1519–1659

B

y the sixteenth century, then, the power struggles within Europe were also helping it to rise, economically and militarily, above the other regions of the globe. What was not yet decided, however, was whether any one of the rival European states could accumulate sufficient resources to surpass the rest, and then dominate them. For about a century and a half after 1500, a continent-wide combination of kingdoms, duchies, and provinces ruled by the Spanish and Austrian members of the Habsburg family threatened to become the predominant political and religious influence in Europe. The story of this prolonged struggle and of the ultimate defeat of these Habsburg ambitions by a coalition of other European states forms the core of this chapter. By 1659, when Spain finally acknowledged defeat in the Treaty of the Pyrenees, the political

plurality

of Europe—containing five or six major states, and various smaller ones—was an indisputable fact. Which of those leading states was going to benefit most from further shifts within the Great Power system can be left to the following chapter; what at least was clear, by the mid-seventeenth century, was that no single dynastic-military bloc was capable of becoming the master of Europe, as had appeared probable on various occasions over the previous decades.

The interlocking campaigns for European predominance which characterize this century and a half differ both in degree and kind, therefore, from the wars of the pre-1500 period. The struggles which had disturbed the peace of Europe over the previous hundred years had been

localized

ones; the clashes between the various Italian states, the rivalry between the English and French crowns, and the wars of the Teutonic Knights against the Lithuanians and the Poles were typical examples.

1

As the sixteenth century unfolded, however, these traditional regional struggles in Europe were either subsumed into or eclipsed by what seemed to contemporaries to be a far larger contest for the mastery of the continent.

Although there were always specific reasons why any particular state was drawn into this larger context, two more general causes were chiefly responsible for the transformation in both the intensity and geographical scope of European warfare. The first of these was the coming of the Reformation—sparked off by Martin Luther’s personal revolt against papal indulgences in 1517—which swiftly added a fierce new dimension to the traditional dynastic rivalries of the continent. For particular socioeconomic reasons, the advent of the Protestant Reformation—and its response, in the form of the Catholic Counter-Reformation against heresy—also tended to divide the southern half of Europe from the north, and the rising, city-based middle classes from the feudal orders, although there were, of course, many exceptions to such general alignments.

2

But the basic point was that “Christendom” had fractured, and that the continent now contained large numbers of individuals drawn into a

transnational

struggle over religious doctrine. Only in the mid-seventeenth century, when men recoiled at the excesses and futility of religious wars, would there arrive a general, if grudging, acknowledgment of the confessional division of Europe.

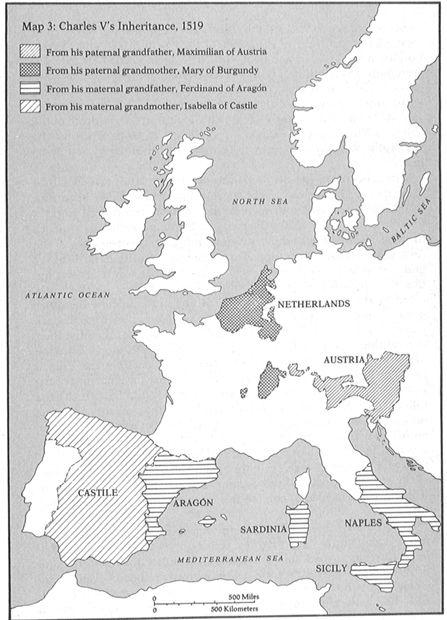

The second reason for the much more widespread and interlinked pattern of warfare after 1500 was the creation of a dynastic combination, that of the Habsburgs, to form a network of territories which stretched from Gibraltar to Hungary and from Sicily to Amsterdam, exceeding in size anything which had been seen in Europe since the time of Charlemagne seven hundred years earlier. Stemming originally from Austria, Habsburg rulers had managed to get themselves regularly elected to the position of Holy Roman emperor—a title much diminished in real power since the high Middle Ages but still sought after by princes eager to play a larger role in German and general European affairs.

More practically, the Habsburgs were without equal in augmenting their territories through marriage and inheritance. One such move, by Maximilian I of Austria (1493–1519, and Holy Roman emperor 1508–1519), had brought in the rich hereditary lands of Burgundy and, with them, the Netherlands in 1477. Another, consequent upon a marriage compact of 1515, was to add the important territories of Hungary and Bohemia; although the former was not within the Holy Roman Empire and possessed many liberties, this gave the Habsburgs a great bloc of lands across central Europe. But the most far-reaching of Maximilian’s dynastic link-ups was the marriage of his son Philip to Joan, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, whose own earlier union had brought together the possessions of Castile and Aragon (which included Naples and Sicily). The “residuary legatee”

3

to all these marriage

compacts was Charles, the eldest son of Philip and Joan. Born in 1500, he became Duke of Burgundy at the age of fifteen and Charles I of Spain a year later, and then—in 1519—he succeeded his paternal grandfather Maximilian I both as Holy Roman emperor and as ruler of the hereditary Habsburg lands in Austria. As the Emperor Charles V, therefore, he embodied all four inheritances until his abdications of 1555–1556 (see Map 3). Only a few years later, in 1526, the death of the childless King Louis of Hungary in the battle of Mohacs against the Turks allowed Charles to claim the crowns of both Hungary and Bohemia.

The sheer heterogeneity and diffusion of these lands, which will be examined further below, might suggest that the Habsburg imperium could never be a real equivalent to the uniform, centralized empires of Asia. Even in the 1520s, Charles was handing over to his younger brother Ferdinand the administration and princely sovereignty of the Austrian hereditary lands, and also of the new acquisitions of Hungary and Bohemia—a recognition, well before Charles’s own abdication, that the Spanish and Austrian inheritances could not be effectively ruled by the same person. Nonetheless, that was

not

how the other princes and states viewed this mighty agglomeration of Habsburg power. To the Valois kings of France, fresh from consolidating their own authority internally and eager to expand into the rich Italian peninsula, Charles V’s possessions seemed to encircle the French state—and it is hardly an exaggeration to say that the chief aim of the French in Europe over the next two centuries would be to break the influence of the Habsburgs. Similarly, the German princes and electors, who had long struggled against the emperor’s having any real authority within Germany itself, could not but be alarmed when they saw Charles V’s position was buttressed by so many additional territories, which might now give him the resources to impose his will. Many of the popes, too, disliked this accumulation of Habsburg power, even if it was often needed to combat the Turks, the Lutherans, and other foes.

Given the rivalries endemic to the European states system, therefore, it was hardly likely that the Habsburgs would remain unchallenged. What turned this potential for conflict into a bitter and prolonged reality was its conjunction with the religious disputes engendered by the Reformation. For the fact was that the most prominent and powerful Habsburg monarchs over this century and a half—the Emperor Charles V himself and his later successor, Ferdinand II (1619–1637), and the Spanish kings Philip II (1556–1598) and Philip IV (1621–1665)—were also the most militant in the defense of Catholicism. As a consequence, it became virtually impossible to separate the power-political from the religious strands of the European rivalries which racked the continent in this period. As any contemporary

could appreciate, had Charles V succeeded in crushing the Protestant princes of Germany in the 1540s, it would have been a victory not only for the Catholic faith but also for Habsburg influence—and the same was true of Philip II’s efforts to suppress the religious unrest in the Netherlands after 1566; and true, for that matter, of the dispatch of the Spanish Armada to invade England in 1588. In sum, national and dynastic rivalries had now fused with religious zeal to make men fight on where earlier they might have been inclined to compromise.

Even so, it may appear a little forced to use the title “The Habsburg Bid for Mastery” to describe the entire period from the accession of Charles V as Holy Roman emperor in 1519 to the Spanish acknowledgment of defeat at the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659. Obviously, their enemies

did

firmly believe that the Habsburg monarchs were bent upon absolute domination. Thus, the Elizabethan writer Francis Bacon could in 1595 luridly describe the “ambition and oppression of Spain”:

France is turned upside down.… Portugal usurped.… The Low Countries warred upon.… The like at this day attempted upon Aragon.… The poor Indians are brought from free men to be slaves.

4

But despite the occasional rhetoric of some Habsburg ministers about a “world monarchy,”

5

there was no conscious plan to dominate Europe in the manner of Napoleon or Hitler. Some of the Habsburg dynastic marriages and successions were fortuitous, at the most inspired, rather than evidence of a long-term scheme of territorial aggrandizement. In certain cases—for example, the frequent French invasions of northern Italy—Habsburg rulers were more provoked than provoking. In the Mediterranean after the 1540s, Spanish and imperial forces were repeatedly placed on the defensive by the operations of a revived Islam.

Nevertheless, the fact remains that had the Habsburg rulers achieved all of their limited, regional aims—even their

defensive

aims—the mastery of Europe would virtually have been theirs. The Ottoman Empire would have been pushed back, along the North African coast and out of eastern Mediterranean waters. Heresy would have been suppressed within Germany. The revolt of the Netherlands would have been crushed. Friendly regimes would have been maintained in France and England. Only Scandinavia, Poland, Muscovy, and the lands still under Ottoman rule would not have been subject to Habsburg power and influence—and the concomitant triumph of the Counter-Reformation. Although Europe even then would not have approached the unity enjoyed by Ming China, the political and religious principles favored by the twin Habsburg centers of Madrid and Vienna

would have greatly eroded the pluralism that had so long been the continent’s most important feature.

The chronology of this century and a half of warfare can be summarized briefly in a work of analysis like this. What probably strikes the eye of the modern reader much more than the names and outcome of various battles (Pavia, Lützen, etc.) is the sheer length of these conflicts. The struggle against the Turks went on decade after decade; Spain’s attempt to crush the Revolt of the Netherlands lasted from the 1560s until 1648, with only a brief intermission, and is referred to in some books as the Eighty Years War; while the great multidimensional conflict undertaken by both Austrian and Spanish Habsburgs against successive coalitions of enemy states from 1618 until the 1648 Peace of Westphalia has always been known as the Thirty Years War. This obviously placed a great emphasis upon the relative

capacities

of the different states to bear the burdens of war, year after year, decade after decade. And the significance of the material and financial underpinnings of war was made the more critical by the fact that it was in this period that there took place a “military revolution” which transformed the nature of fighting and made it much more expensive than hitherto. The reasons for that change, and the chief features of it, will be discussed shortly. But even before going into a brief outline of events, it is as well to know that the military encounters of (say) the 1520s would appear very small-scale, in terms of both men and money deployed, compared with those of the 1630s.

The first series of major wars focused upon Italy, whose rich and vulnerable city-states had tempted the French monarchs to invade as early as 1494—and, with equal predictability, had produced various coalitions of rival powers (Spain, the Austrian Habsburgs, even England) to force the French to withdraw.

6

In 1519, Spain and France were still quarreling over the latter’s claim to Milan when the news arrived of Charles V’s election as Holy Roman emperor and of his combined inheritance of the Spanish and Austrian territories of the Habsburg family. This accumulation of titles by his archrival drove the ambitious French king, Francis I (1515–1547), to instigate a whole series of countermoves, not just in Italy itself, but also along the borders of Burgundy, the southern Netherlands, and Spain. Francis I’s own plunge into Italy ended in his defeat and capture at the battle of Pavia (1525), but within another four years the French monarch was again leading an army into Italy—and was again checked by Habsburg forces. Although Francis once more renounced his claims to Italy at the 1529 Treaty of Cambrai, he was at war with Charles V over those possessions both in the 1530s and in the 1540s.